A Confluence of Peregrinations and Prayers

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

A blurring of boundaries, personal and political.

BY LAURA J. COLE | October 18, 2023

I was driving west from Florida on interstates that snaked beside parts of the 2,170 miles that was once the Oregon Trail.

The particular direction of this route was new to me, but driving across the country was not. I had twice crisscrossed the full width of the North American continent before beginning this particular trek, towing what remained of my belongings past prairie that turned into desert that turned into mountains into grasslands then forests. Only when Mt. Hood was behind me did I allow myself to call this place my new home.

I hadn’t yet decided on which side of the Columbia I’d land, but I was excited about a dream 14 years in the making finally becoming a reality. It was then that I first truly considered what exactly was the Pacific Northwest, by which I really meant, where does it begin and end? What are the boundaries and borders?

In his book Arctic Dreams, Pacific Northwest nature writer Barry Lopez wrote: “As I moved through the Arctic I thought often about a rhythm indigenous to this land, not one imposed on it. The imposed view, however innocent, always obscures. … To understand why a region is different, to show an initial deference toward its mysteries, is to guard against a kind of provincialism that vitiates the imagination, that stifles the capacity to envision what is different.”

Rather than imposing and obscuring, I wanted and want to understand what this region means to the people who have called it home long before me. The thing that drew me to this place was the confluence of possibilities: city and desert, mountains and ocean. That was my first experience of the Pacific Northwest, anyway. In 2008, I flew out here to celebrate a friend’s baby shower in Seattle. I, like I imagine so many others, fell in love with the idea that only an hour or two from the city, you could be hiking a mountain, wandering in a rainforest, traversing a desert, or watching whales breach the surface of the sea.

I suppose possibility is what draws most people to a place. The possibility for economic and social mobility, certainly, but also the possibility to start over. The possibility of becoming. For me, it was the latter, plus, admittedly, a more tangible desire to spend time outside without constantly sweating.

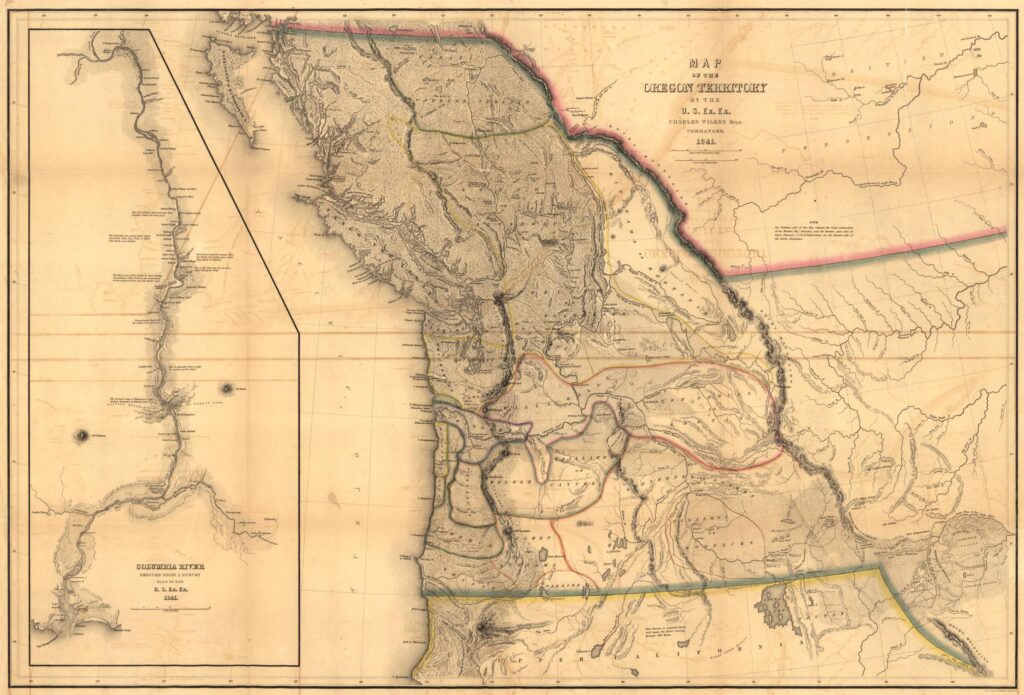

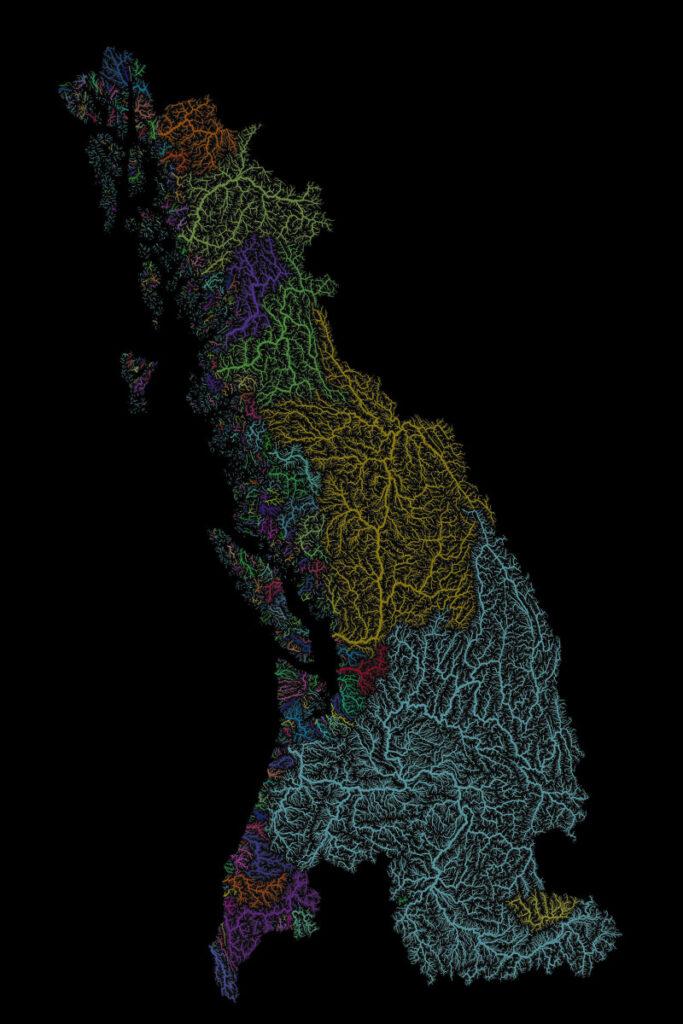

A map of the Oregon Territory from 1841 includes territories for the Chinook, Cowlitz, Dakelh, Kootenai, Salish, Nez Perce, Shoshone, Umpqua, and Walla Walla indigenous people, among others, as well as a map of the Columbia River.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

What I naively thought would be a simple answer has been anything but. If anything those borders and boundaries have blurred rather than sharpened.

It’s been a year since I began wondering what it means to be “of” the Pacific Northwest. What I naively thought would be a simple answer has been anything but. If anything those borders and boundaries have blurred rather than sharpened. In searching, I’ve found that Oregon and Washington are the two states always included, though not always all of both. I’ve found maps that carve out a swatch of southeast Oregon in exchange for part of northern California, maps that include Idaho and parts of Montana and British Columbia, and others that extend all the way into Alaska and the Yukon territory.

The latter seems the most closely aligned with what was originally the Oregon Territory. In 1838, it spanned from British Columbia in the north to northern California in the south and just east of the current state borders of Minnesota and Iowa in the U.S. up through Manitoba. That territory would shrink west in 1846 to the British Columbia-Alberta border but still include the western-most parts of Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado. At the time, it was known as the “Oregon Question,” with the United States and Britain disputing what lands belonged to each nation—and ignoring the various tribes that long lived spread out across all of it.

A map of the Oregon Territory from 1841 includes territories for the Chinook, Cowlitz, Dakelh, Kootenai, Salish, Nez Perce, Shoshone, Umpqua, and Walla Walla indigenous people, among others, as well as a map of the Columbia River.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

In 1888, John Hyde wrote Wonderland; or The Pacific Northwest and Alaska, a pamphlet encouraging travel along the Northern Pacific Railroad. In it, he wrote, “It is doubtful whether, of the 25,000 Americans who visited Europe during the summer of 1887, one in a hundred had ever gazed upon the mysterious and awe-inspiring scenes of that greatest of the world’s natural wonders, the Yellowstone National Park; or whether even one in a thousand had experienced that indescribable exaltation of feeling which takes possession of the traveler as he looks for the first time upon the mountains and glaciers of imperial Alaska.”

According to Peter Stark in Astoria, “Britain wanted [the border] drawn at the Columbia River (the border between today’s Washington and Oregon), while the more adamant U.S. advocates demanded that the United States take all the Pacific Coast as far north as the Russian posts in Alaska at about 54 degrees, 40 minutes north—thus the rallying cry of the American advocates of Manifest Destiny, ‘Fifty-four forty or fight!’ ”

If the U.S. had won that compromise, Alaska might connect to the Lower 48, as the 54th parallel runs near the state’s southern-most border. Instead, Britain and the U.S. compromised at 49 degrees north—the current U.S.-Canada border.

In the late nineteenth century, the railroads began to promote “The Pacific Northwest” as a place worth visiting or settling down, and the moniker for the region was born. In 1888, Rand McNally published John Hyde’s Wonderland; or the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. (Perhaps inspiring the popular hashtag PNWonderland). It is essentially an extended ad for “The Wonderland Route to the Pacific Coast,” arguing that North America is as worthy of seeing and exploring as Europe, a claim with which I wholeheartedly agree, and including various costs of ticket fares.

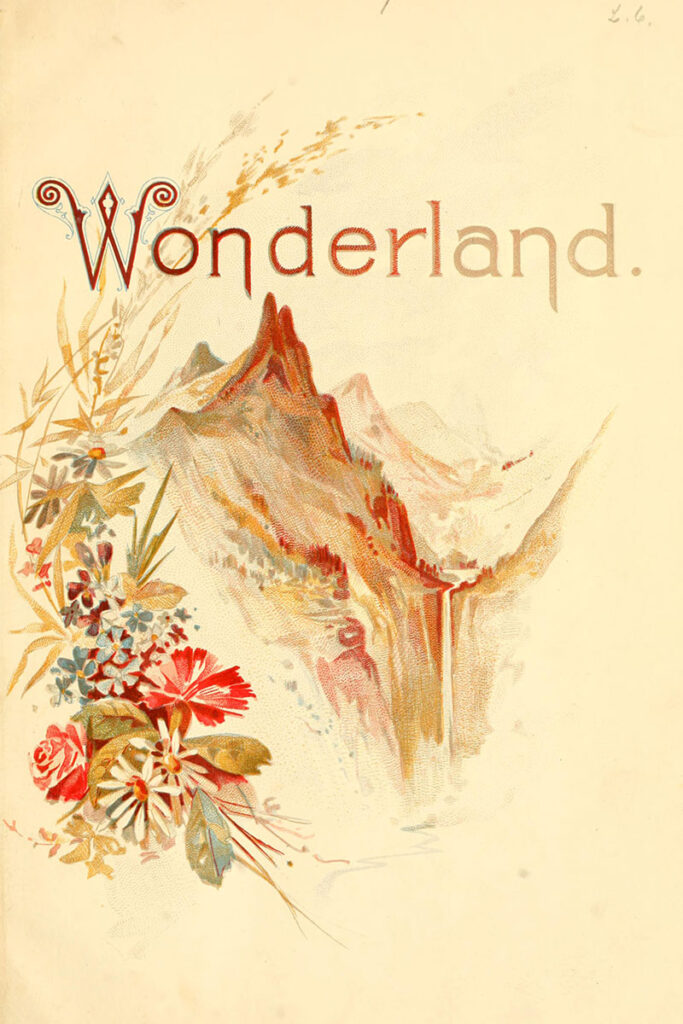

Nearly a century later, the term Cascadia emerged to describe the geology of the Pacific Northwest and a possibility for a region based on it. Bates McKee used it in 1972 in his book, Cascadia: The Geologic Evolution of the Pacific Northwest. It’s a nod to the mountain range of volcanoes that includes Lassen, Three Sisters, Hood, Rainier, and Baker. But according to David McCloskey, a former sociology professor at Seattle University, the region is more defined by water than fire. He evolved the term to describe and map the “land of falling waters,” a place made up of 75 distinct ecoregions and defined by the watersheds that run toward the Pacific Ocean from northern California to southern Alaska and inland as far as the Continental Divide.

“Water is the voice of this place, sets the land to singing, the voice that calls life into the place, and invites the people to dwell.”

“Water is the voice of this place, sets the land to singing, the voice that calls life into the place, and invites the people to dwell,” it says on the website for the Cascadia Institute, which McCloskey founded. “Cascades are the mountains breaking into song.”

I am intrigued by the idea of a region defined by watersheds rather than geopolitics, even if some of the waterways have been forcibly altered by humans—and our politics. The possibilities of a place expand when highlighted with rivers rather than outlined by borders.

The imagination does, too. The focus shifts from attempting to establish the facts of a place to do what rivers do: rage and wane, bend and flow, return and remember. It’s a both/and mentality that presents perpetual harbingers of possibility along a journey of discovering rivers, a region, and maybe, just maybe, my potential in this new place.

Cascadia, a region defined by geology

According to David McCloskey, “Cascadia is a land rooted in the very bones of the earth, and animated by the turnings of sea and sky, the mid-latitude wash of winds and waters. Cascade arises from both a natural integrity (e.g. landforms and earth-plates, weather patterns and ocean currents, watersheds, flora, fauna, etc.) and a sociocultural unity (e.g. native cultures, a shared history and destiny).”

In 2019, the geographer Szűcs Róber created a watershed map of Cascade. Called the Cascade Hydrological Map, it shows the series of rivers that make up the Cascade bioregion sans national borders to highlight the interconnected streams, rivers, and waterways, including the Columbia, Fraser, and Snake rivers.

Image by Cascadia Illahee or Department of Bioregion

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

Located near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, the Vancouver Land Bridge merges rivers, land, people, and trade.