A Confluence of Peregrinations and Prayers

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

Located near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, the Vancouver Land Bridge merges rivers, land, people, and trade.

This essay is part of a series on Maya Lin’s Confluence Project, in which I explore the history, heritage, and ecology of five existing sites. You can read more by visiting the Confluence Project series page.

BY LAURA J. COLE | October 30, 2024

Cars roar by on the Lewis and Clark Highway. An exasperated, idling cargo train releases short, frequent bursts of steam. Propeller planes take off and land in a howling crescendo.

The constant cacophony is overwhelming at what is easily the noisiest and most urban of the Confluence sites. I wonder what this place would be like without all of it, with only the sounds of nature. But the thrum of people and their constant activity is no stranger here. Long before Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery stopped here in the 1800s, this spot was a significant gathering place and trading post. It was full of people bartering, haggling, negotiating, perhaps gossiping, and certainly catching up with family and friends.

Halfway between the mouth of the Columbia River and Celilo Falls, the location was part of a vast trade network that stretched from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. Commodities ranged from shells and whale oil from the ocean to bison robes and horses from the prairies. It also included the food that sustained Indigenous populations across this region, such as camas root and wapato.

The latter, which is also known as duck potato and arrowroot, once grew in abundance in this area and along nearby Sauvie Island (formerly known as Wapato Island).

After eating some with sturgeon, William Clark described how women would harvest the root. Wading into the water, sometimes up to their necks, and holding onto the side of a canoe, Indigenous women would use their toes to loosen and pull up the bulbs. Lewis recorded how valuable the vegetable was considered: “the wappetoe furnishes the principal article of traffic with these people which they dispose of to the nations below in exchange for beads cloth and various articles,” he wrote. “[T]he natives of the Sea coast and lower part of the river will dispose of their most valuable articles to obtain this root.”

Indigenous land of:

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

Cowlitz

Image courtesy of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The thrum of people and their constant activity is no stranger here.

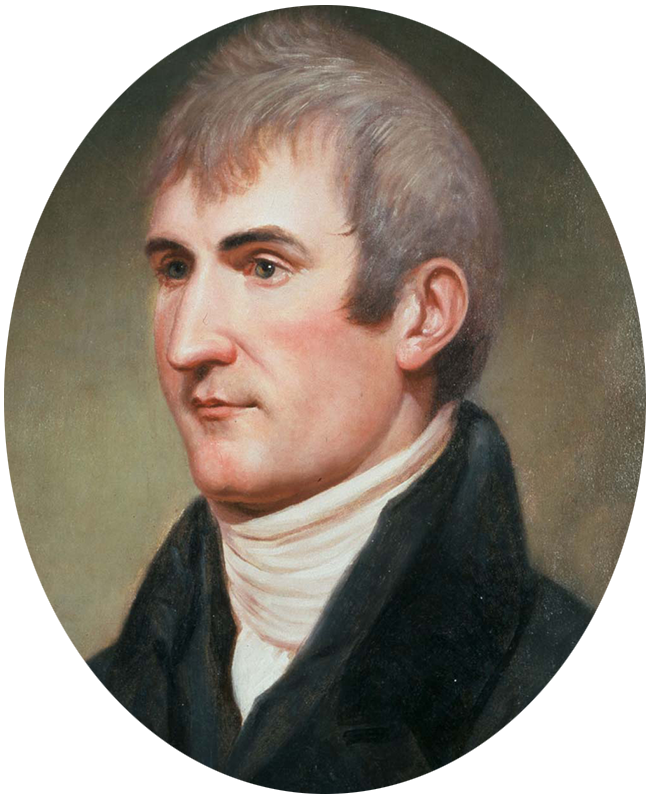

So much has changed in this location since 1806 when Meriwether Lewis and Clark spent the night on these shores—arguably more than at any of the other Confluence sites. But what is interesting and lovely about this one is how it connects river, land, and people.

A 40-foot wide pedestrian crossing, the Vancouver Land Bridge can be entered from the side nearest Fort Vancouver or the side closest to the Columbia River. For the latter, you walk beneath railroad tracks then through another portal: A welcome gate designed by Pacific Northwest Native American artist Lillian Pitt. At the top of the gate are two crossed oars made of western red cedar, reminders of how travelers once arrived here by canoe made of the same wood. Embedded in each oar is a glass face modeled on women from tribes of the lower Columbia River.

“The image is a Chinook woman, in honor of the significant role women played, not only in food gathering and preparation but in the vital trade networks up and down the river. It was the women who negotiated deals,” Colin Fogerty, former executive director of the Confluence Project, says in an audio tour.

The next stop takes you to the top of the bridge and the first of three overlooks. Pitt designed these as “Spirit Baskets,” combining elements of woven baskets—made by women to gather, carry, and even cook goods—with figures inspired by the Columbia River petroglyphs, such as Tsagaglalal, a female Indigenous spirit known as “She Who Watches.”

“These artists etched out thousands upon thousands of pictographs and petroglyphs up and down the Big River,” Pitt said in an artist statement. “Most of them are underwater now, on account of the dams that were built, but many of them are still visible today.”

Indigenous land of:

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

Cowlitz

Solid green marks treaty areas and striped green marks the unheeded territory of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde.

Image courtesy of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The top of each basket—or overlook—is circled in stainless steel, each location with a different focus and its equivalent word in nine native languages. The first is River. Nchi’-i-Wàna. Wimal. Signs encourage you to look out over the Columbia River. The river’s proximity is what made this place first a center for trade, then a fort, and now a thoroughfare for planes, trains, and automobiles. A large cargo train blocked my view, but I knew the river was there, even though I could not see or hear it.

Continuing north over Highway 14, the next overlook is focused on Land. Ticham. Limksh. On my recent visit, it was gray and overcast. I could not see any of the surrounding mountains the signs point out: mounts Hood, Saint Helens, Adams, Rainier, and Jefferson. The large fields of grass surrounding Fort Vancouver and Pearson Air Field were golden, and both leaves and stalks alike drooped from the heat and lack of rain. It felt as though everything was leaning toward decay, including the bridge itself, which has cracks, peeling paint, and black soot. The rain is hard on the structures we build; its absence difficult on the environment we do not.

The plants, like the land itself, were in flux. I like to imagine what this place looked like in the past, choosing to picture it closer to how it appeared when I first visited, on a Saturday in springtime. Then, everything was green and lush and blooming. It was bustling with people biking, walking, and jogging. The signs spread throughout the land bridge pointed out the plants flourishing along its edges: red alder, nootka rose, Oregon grape.

“My work is a delicate plea for responsible conduct toward the environment.”

—Lillian Pitt

The bridge architect Johnpaul Jones stated that his structure “completes a circle that’s been broken.” Part of that is a physical connection between the water’s edge and the land where a market once flourished. But more importantly, it’s a connection to the final overlook’s focus: People. Nimiipuu. Tiinma. Especially the people who lived along the Columbia River Gorge for more than 10,000 years before the Lewis and Clark expedition.

It’s a reminder of all that has been forcibly erased and replaced, including the connection between the tribes, the rivers, and the land. How they depended on both and knew when and where to gather wapato, harvest camas, and catch salmon. They flowed along the land and the river in harmony with that knowledge.

“My work is a delicate plea for responsible conduct toward the environment,” Pitt said.

It makes sense, then, that this final overlook, the one dedicated to people, is the one closest to the land, where Indigenous history runs as deep—and sadly, often unseen—as the wapato bulbs that Indigenous women once used their toes to discover and root out.

Journal entry

March 30, 1806

“We had a view of mount St. helines and Mount Hood. the 1st is the most noble looking object of it’s kind in nature. … this valley would be copetent to the mantainance of 40 or 50 thousand souls if properly cultivated and is indeed the only desireable situation for a settlement which I have seen on the West side of the Rocky mountains.”

— Meriwether Lewis

Did you know?

Located in an area known by the Klickitat people as Alaek-ae (the place of the mud turtles) and by fur trappers as Jolie Prairie, Fort Vancouver was established in 1825 by the Hudson’s Bay Company to serve as the headquarters for the company’s operations west of the Rocky Mountains, which spanned from Russian Alaska in the north to Mexican California in the south. A major center of industry, trade, and law, the fort once marked the end of the Oregon Trail, but burned to the ground in 1866. It was later excavated and reconstructed in the mid-1900s.

Image courtesy of Library of Congress

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

Located near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, the Vancouver Land Bridge merges rivers, land, people, and trade.