A Confluence of Peregrinations and Prayers

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

BY LAURA J. COLE | March 5, 2025

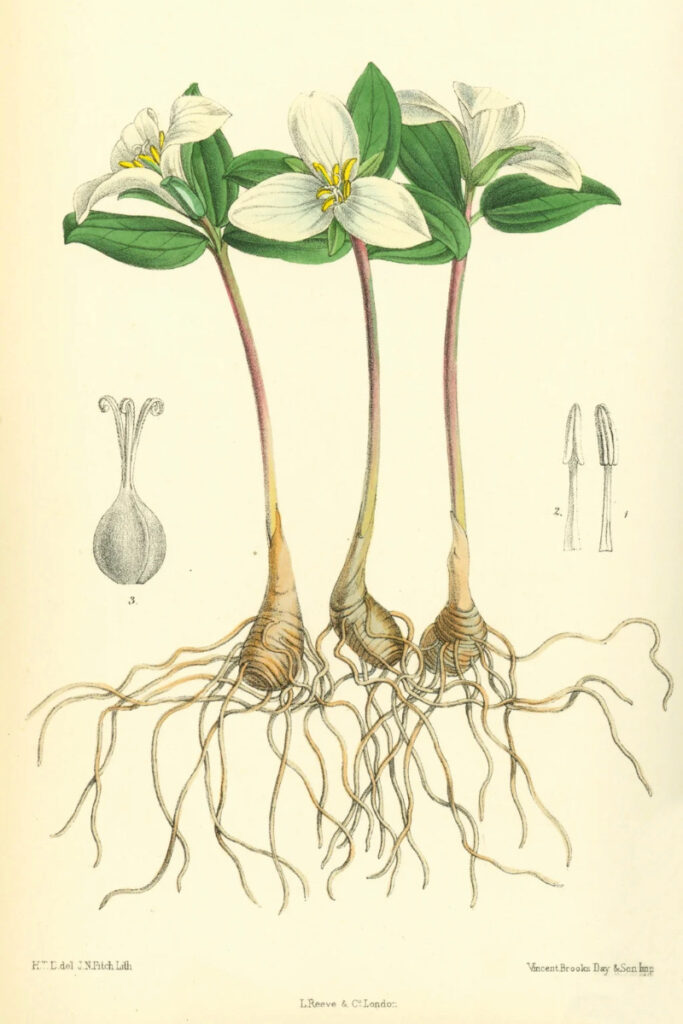

Women of both the Makah and Quinault tribes believed the bulb could be used as a love potion to gain the affection of desired partners. Elder members of the Quinault tribe would warn children that picking the flower would make it rain—an undesirable outcome since trilliums begin blooming in mid-winter or early spring, when most people in the Pacific Northwest yearn for sunshine. And a myth told by white people, possibly started because fines were once imposed for doing so, purports that if you pick the flower, which in these parts can live for over 50 years, another blossom will not appear for seven years. The plant, roots and all, so goes the tale, will die entirely.

The latter seems rampant, found in searches for the flower and even appearing in a Facebook post that came across my feed and initially piqued my interest. Those legends are unsurprising for a beloved ephemeral bloom whose genus ranges across North America—spreading east from British Columbia to Newfoundland in the north down to central California and northern Florida in the south—and Asia, where it spans from the Himalayas all the way to the Kuril Islands.

The specific species of Trillium ovatum, found only out West, grows from Vancouver Island in British Columbia south to Monterrey County in California. Though the flower has grown here for millennia, Meriwether Lewis first plucked one for cataloging on April 10, 1806, while journeying along the rapids of the Columbia River.

Nearly two centuries later, I encountered the first one I recall ever seeing along the trail at the top of Multnomah Falls on April 30, 2022. I know because I entered the photo I snapped into my flower identification app, PictureThis, on that date. The act is part of my process to learn the names of the blossoms and blooms I encounter, which began in 2020 during my travels across North America. On my journey out West, for example, I chased rabbitbrush and fireweed, chokecherries and plumed cockscomb. And as I scroll through “My Plants” in the app, the snowy white blossom of the western trillium is there among the yellow Western skunk cabbage, an almost magenta salmonberry, and a red flowering dogwood that I encountered the same week.

Native Names for the Pacific Trillium

Lummi: tcelta’les

Makah: tcatca’ol!us, “sad flower”

Quileute: kokots’tada’ktci, “thieves’ leaves”

Skagit: x!at’t!ek’

Snohomish: tcu’xtcob (generic word for flower)

From Ethnobotany of Western Washington: The Knowledge and Use of Indigenous Plants by Native Americans by Erna Gunther

Shakespeare’s Juliet mused, “What’s in a name?,” and for me, there’s delight in unearthing the origins of words and the stories and history surrounding objects we often take for granted. It’s the keepsake that lasts far longer than the short-lived flower itself. For example, another name for the flower is the Pacific wake robin, so named because the flowers bloom in early spring just as the robins begin to return or “wake up.” And the Latin word it’s named for, trillium, means “in threes” and ovatum means “egg-shaped.” Looking closely at it, you can’t help but notice its series of trinities: the three yellow stigmas, followed by three white—or pink or purple, depending on where it is in its lifecycle—petals, followed by a whorl of three green sepals and three green leaves.

As the saying goes, good things come in threes (derived from the Latin omne trium perfectum or “everything that is three is perfect”), and though the plant is less commonly used today for medicinal purposes, that wasn’t always the case.

According to Profiles of Northwest Plants, “The early white settlers called the plant ‘birth root’ because they thought that the Indians used it to induce labor. Instead the Indians used it to stop bleeding after childbirth or to stop menstrual hemorrhages. Western medicine also employed it for this purpose for a time.” The plant has also been used by tribes as an eye medicine; to stop uterine, respiratory tract, and urinary tract bleeding; and for coughs, bronchial problems, pulmonary consumption, and diarrhea.

The early white settlers called the plant ‘birth root’ because they thought that the native peoples used it to induce labor.

Medicinal applications of the plant have dwindled since plant-based products became regulated under the Dietary Supplement Act, passed in 1994. But its hold on our imagination has not.

It’s likely the bulb won’t bewitch a suitor or that picking one will bring the rains—they’re likely to come in these parts, regardless. But picking its flower certainly won’t kill the plant.

“It is possible this ‘myth’ is widely spread in an effort to discourage people from picking them in the wild. This is an understandable approach,” says Signe Danler, an instructor at Oregon State University’s Master Gardener Online program. “While picking a flower won’t kill the plant, it reduces the number of seeds produced, hence potentially reducing the population.”

And picking the flower will certainly reduce the number of people who could otherwise enjoy it—and hence, their curiosity to root out some of the stories we share about it.

If you pick a trillium flower, the plant dies.

False. Picking the flower can potentially impact the plant’s growth, but mature plants have substantial roots, which help them survive the winter and fires.

It is illegal to pick a trillium.

True and false. It is illegal to pick or collect plants without a permit in any National Forest, Park, or Monument. In Oregon, it is illegal to pick any plant within 500 feet of a public highway. And in Washington, it is illegal to pick any native flowering plant growing along a public street or highway, and in state and city parks. The rest is a gray area, but there are significant ecological reasons not to, so maybe don’t.

It takes seven years for a trillium to bloom if picked.

True and false. It is true that it can take a trillium seven to eight years to produce its first flower under ideal conditions and up to a decade otherwise, but the plants typically bloom every year after that, even some whose flowers were picked the previous year.

Trillium roots were once used to treat wounds during childbirth.

True. The roots were used during and after birth and for preventing and mitigating hemorrhages during childbirth, hence the plant’s popular name: birth root.

Trilliums can be pink.

True. The petals turn pink to purple as the flower ages. There is also a pink trillium that is native to eastern North America, as well as several varieties that are red, green, and yellow.

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

Located near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, the Vancouver Land Bridge merges rivers, land, people, and trade.