A Confluence of Peregrinations and Prayers

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

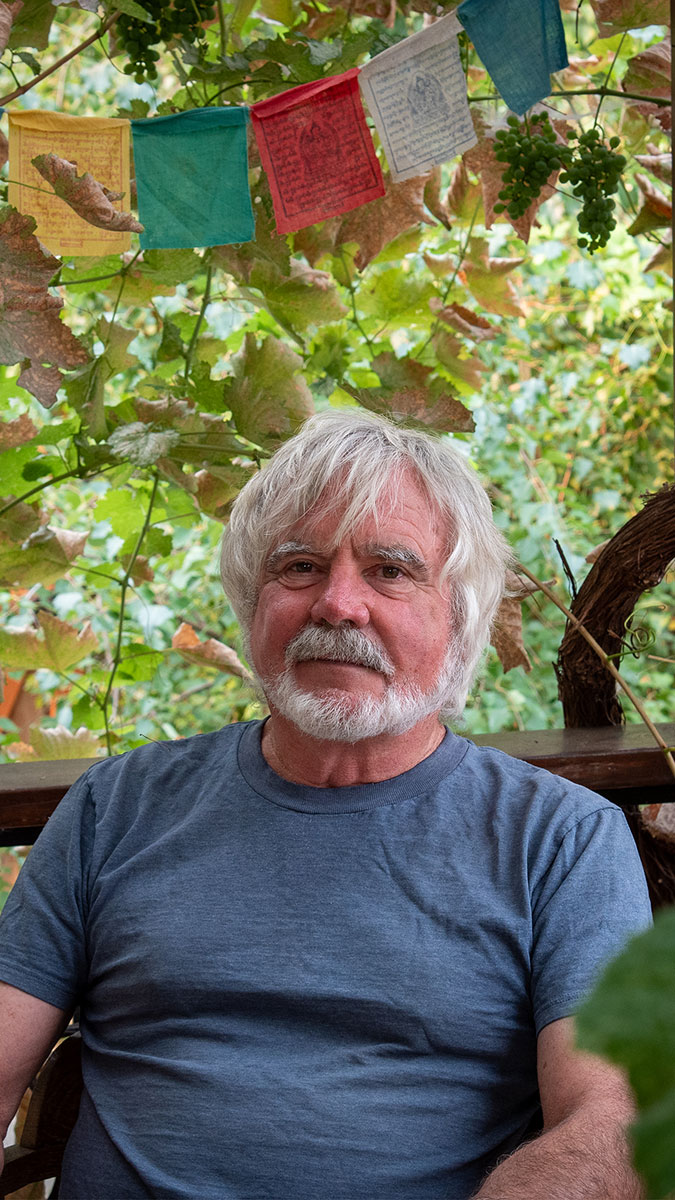

For Gary Koehler, a big-cat expert and retired wildlife researcher from Wenatchee, Washington, home means learning to share the mountains and valleys with all of its enigmatic critters.

BY LAURA J. COLE | October 25, 2023

For Gary Koehler, a big-cat expert and retired wildlife researcher from Wenatchee, Washington, home means learning to share the mountains and valleys with all of its enigmatic critters.

BY LAURA J. COLE | October 25, 2023

“I’ve always been enchanted by the blank spots on the map and the enigmatic predators that accompany them,” says Gary Koehler.

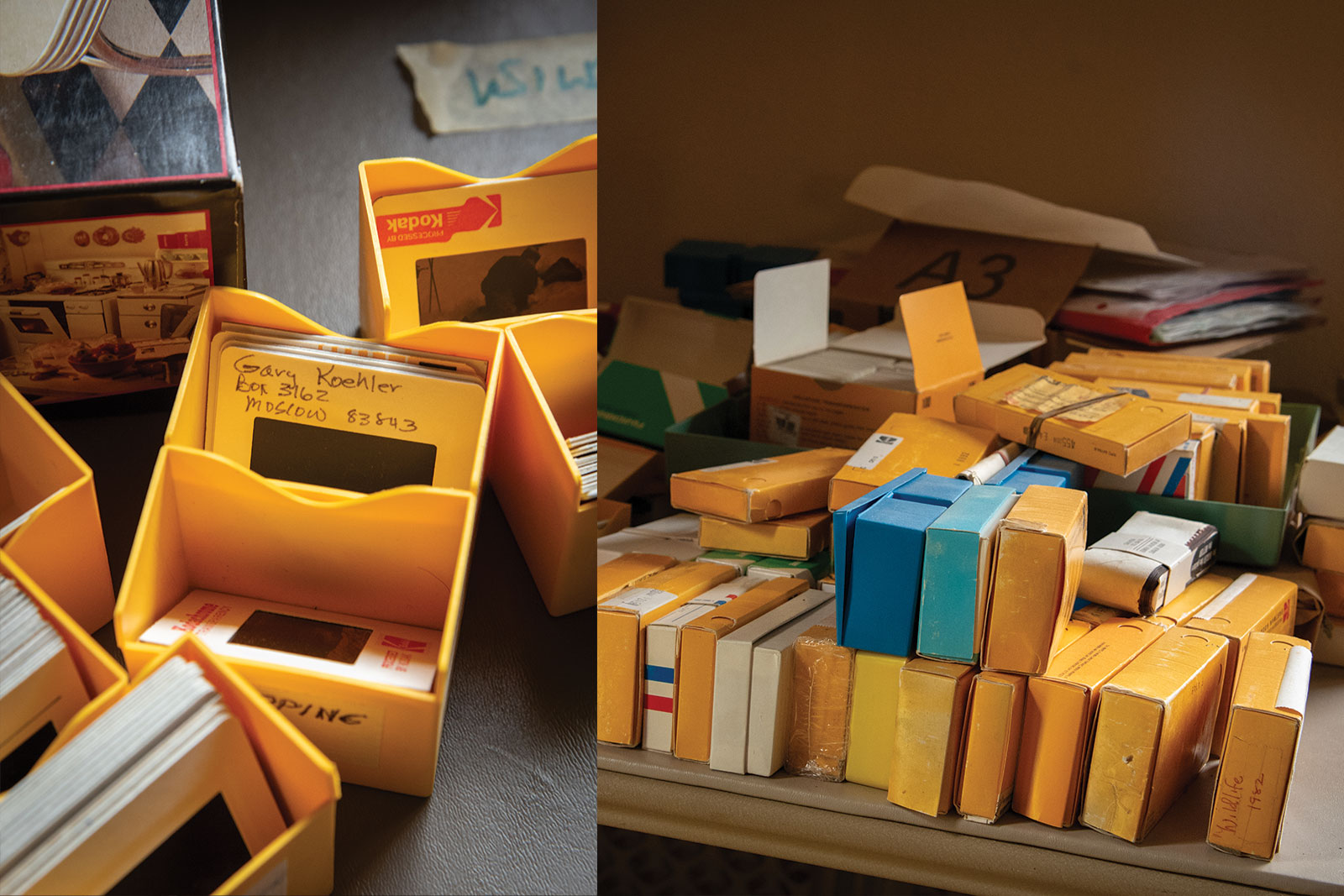

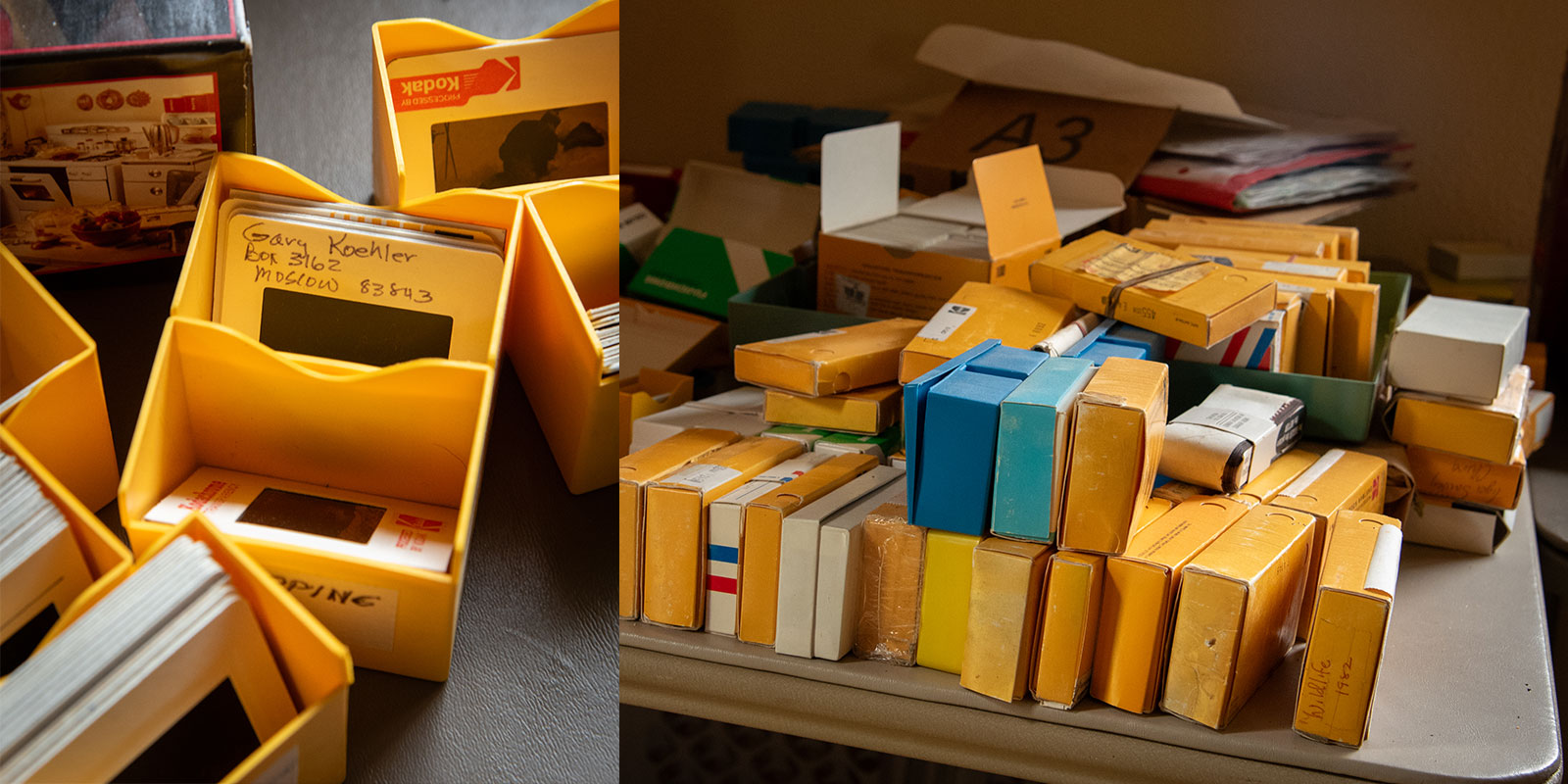

Huddled around his laptop in the dining room of his home in Wenatchee, Washington, I listen alongside his wife, his sister-in-law, and my partner, as Koehler shares stories and photos from his life’s work as a big-cat expert and wildlife researcher. A table behind him is covered in boxes with film slides and negatives with handwritten labels, which he has on his to-do list to scan and digitize: Wildlife 1982, Cascades Hike 1989, Tiger Survey China, Lynx. On the wall in front of him is a colorful tapestry given to him as a thank you gift for helping set up the South China tiger preserve at Laohu Valley Reserve in South Africa. And on the other side of the kitchen, his dogs—three setters named Sig, Max, and Chai—are splayed out, asleep on the floor.

Koehler is practicing a presentation he has been asked to give as part of a three-day celebration of his mentor Maurice Hornocker at the University of Idaho. In many ways, Hornocker launched Koehler’s career studying cougars, African lions, South China tigers, Canadian lynx, snow leopards, bobcats, black bears, wolverines, coyotes, and pine martens, among others—all of which Koehler broadly refers to as “critters.”

In the ‘60s, Maurice Hornocker led a groundbreaking study on mountain lions in Idaho.

More accurately, an article Hornocker wrote launched Koehler’s career.

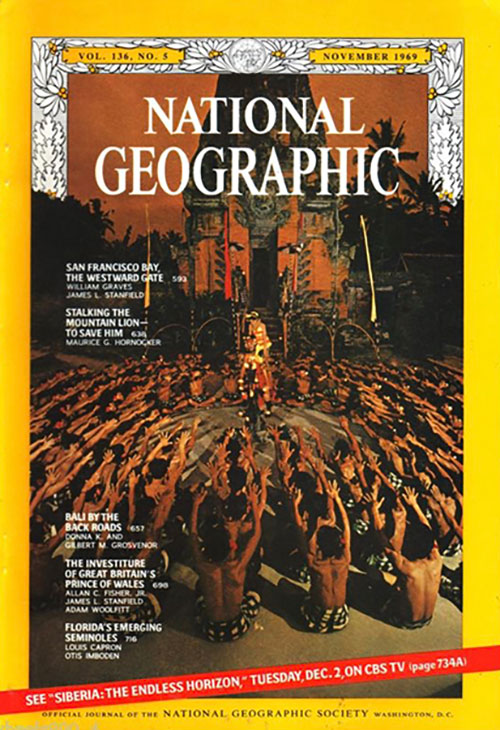

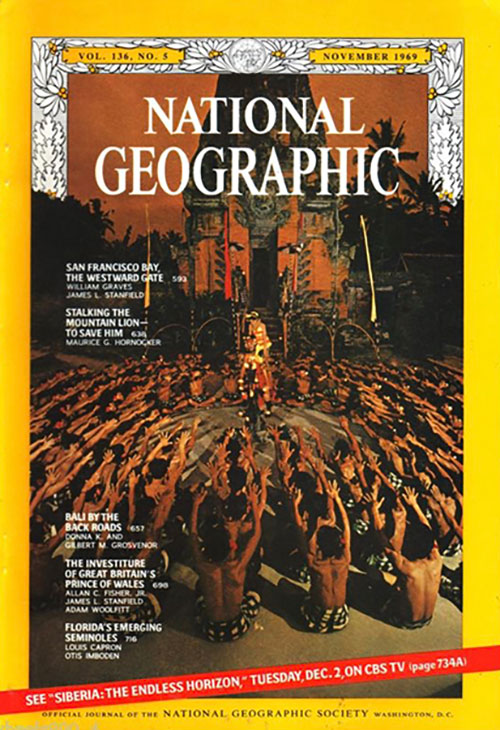

The piece was featured on the cover of the November 1969 issue of National Geographic: “Stalking the Mountain Lion—to Save Him.” In it, Hornocker tells the story of his adventures studying the mountain lion, a cat native to the Americas that ranges from the northern area of British Columbia in Canada to the Strait of Magellan along the southern tip of Chile—the largest geographic range of any nonhuman land mammal in the Western Hemisphere.

Their large range is perhaps the reason for Puma concolor’s many monikers, as many as 40 in English—earning it the title of mammal with the most names from Guinness World Records—including cougar, panther, mountain lion, puma, catamount (short for cat-of-the-mountain), painter, “ghost of the Rockies,” red tiger, and mountain screamer. Koehler uses cougar, a name more common in the Pacific Northwest where he grew up, while Hornocker uses mountain lion, which is more common in the Rocky Mountain West.

“For five years, starting in 1964, Wilbur [Wiles] and I have tranquilized, examined, weighed, marked, and released 46 different lions, many of them again and again, to learn about their lives, their movements, and their habits,” Hornocker wrote in the article. “We have trekked more than 5,000 miles, much of the time on snowshoes, to follow the big cats deep into the Idaho Primitive Area, a 1.2-million-acre federal preserve of wilderness just south of the Salmon River in the central part of the state.”

The article came out not long after Koehler had graduated with a degree in biology from Western Washington University in Bellingham, Washington, near where he grew up in the small town of Deming. He was working as a wilderness ranger in what only a year prior had become North Cascades National Park.

“I had made it into the eastern part of the North Cascades in the Okanagan country and was still looking towards the horizon when Maurice’s article came out,” he says. “There was a picture that really captured my attention—of Maurice’s partner, Wilbur, lowering from the tree an immobilized cat. And I thought, ‘That’s what I want to be.’”

“THERE WAS A PICTURE

THAT REALLY CAPTURED

MY ATTENTION … AND I

THOUGHT, ‘THAT’S WHAT I

WANT TO BE.’”

More accurately, an article Hornocker wrote launched Koehler’s career.

The piece was featured on the cover of the November 1969 issue of National Geographic: “Stalking the Mountain Lion—to Save Him.” In it, Hornocker tells the story of his adventures studying the mountain lion, a cat native to the Americas that ranges from the northern area of British Columbia in Canada to the Strait of Magellan along the southern tip of Chile—the largest geographic range of any nonhuman land mammal in the Western Hemisphere.

Their large range is perhaps the reason for Puma concolor’s many monikers, as many as 40 in English—earning it the title of mammal with the most names from Guinness World Records—including cougar, panther, mountain lion, puma, catamount (short for cat-of-the-mountain), painter, “ghost of the Rockies,” red tiger, and mountain screamer. Koehler uses cougar, a name more common in the Pacific Northwest where he grew up, while Hornocker uses mountain lion, which is more common in the Rocky Mountain West.

“For five years, starting in 1964, Wilbur [Wiles] and I have tranquilized, examined, weighed, marked, and released 46 different lions, many of them again and again, to learn about their lives, their movements, and their habits,” Hornocker wrote in the article. “We have trekked more than 5,000 miles, much of the time on snowshoes, to follow the big cats deep into the Idaho Primitive Area, a 1.2-million-acre federal preserve of wilderness just south of the Salmon River in the central part of the state.”

“THERE WAS A PICTURE

THAT REALLY CAPTURED

MY ATTENTION … AND I

THOUGHT, ‘THAT’S WHAT I

WANT TO BE.’”

The article came out not long after Koehler had graduated with a degree in biology from Western Washington University in Bellingham, Washington, near where he grew up in the small town of Deming. He was working as a wilderness ranger in what only a year prior had become North Cascades National Park.

“I had made it into the eastern part of the North Cascades in the Okanagan country and was still looking towards the horizon when Maurice’s article came out,” he says. “There was a picture that really captured my attention—of Maurice’s partner, Wilbur, lowering from the tree an immobilized cat. And I thought, ‘That’s what I want to be.’”

And that, indeed, is what Koehler became.

In 2011, he retired after 17 years as a wildlife research scientist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, where he studied cougars, black bears, and lynx, and started Project CAT, a citizen science program, with the Cle Elum-Roslyn School District. Since “retiring,” Koehler has been invited to track snow leopards in Mongolia, India, and Nepal, to help set up Laohu Valley Reserve in South Africa, and to study sloth bears in Central India.

While assisting with the latter, a Bengal tiger got caught in one of the live traps—not far from a village—intended for a sloth bear. Koehler recalls hearing the tiger roaring. He climbed aboard an elephant, sandwiched between a handler and the research lead, to try to tranquilize the tiger with a dart gun.

“As we approached the trap with the tiger, the elephant became very uneasy,” says Koehler, who is quiet and unassuming, and whose voice and cadence sound not unlike Nick Offerman’s. “The handler was having a difficult time steering the elephant close to the tiger for darting. As the handler attempted to encourage the elephant to approach the tiger, the elephant began picking up rocks with its trunk and flung them at the secured tiger. After the chastised elephant was coaxed within range for the tranquilizer gun, I darted the belligerent cat, which required a second darting to adequately immobilize for handling and attaching with a radio transmitter collar.”

When his sister-in-law, Mindy, encourages him to share about the time a big cat was right outside their tent, Koehler responds, “Which time?”

And that, indeed, is what Koehler became.

In 2011, he retired after 17 years as a wildlife research scientist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, where he studied cougars, black bears, and lynx, and started Project CAT, a citizen science program, with the Cle Elum-Roslyn School District. Since “retiring,” Koehler has been invited to track snow leopards in Mongolia, India, and Nepal, to help set up Laohu Valley Reserve in South Africa, and to study sloth bears in Central India.

While assisting with the latter, a Bengal tiger got caught in one of the live traps—not far from a village—intended for a sloth bear. Koehler recalls hearing the tiger roaring. He climbed aboard an elephant, sandwiched between a handler and the research lead, to try to tranquilize the tiger with a dart gun.

“As we approached the trap with the tiger, the elephant became very uneasy,” says Koehler, who is quiet and unassuming, and whose voice and cadence sound not unlike Nick Offerman’s. “The handler was having a difficult time steering the elephant close to the tiger for darting. As the handler attempted to encourage the elephant to approach the tiger, the elephant began picking up rocks with its trunk and flung them at the secured tiger. After the chastised elephant was coaxed within range for the tranquilizer gun, I darted the belligerent cat, which required a second darting to adequately immobilize for handling and attaching with a radio transmitter collar.”

When his sister-in-law, Mindy, encourages him to share about the time a big cat was right outside their tent, Koehler responds, “Which time?”

For three years, Koehler studied lions through Moi University in Kenya.

One was while deep in the Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya. That night, three lionesses and a lion walked into the campsite where he was staying with his wife, Mona, and a group of researchers. This was in the early 1990s, when Koehler had been invited to address issues with lions attacking the Maasai’s herds of cattle and goats, as well as to work with graduate students while developing a master’s in wildlife program at Moi University. Mona, a registered nurse with a background in public health, was helping establish their medical program.

Back then, before DNA analysis, he says the only way they could distinguish lions was by recording the unique pattern of whisker spots, which are as unique as an individual’s fingerprint. That night, he looked up and saw rather than heard the lions in their campsite. Cats—even the big ones—have a feline way of moving without making a sound. The pride was only 30 or 40 yards away, and all that stood between them was the equivalent of a thin mosquito net.

“Then the lion roared, and it was so loud it shook the ground beneath us,” says Mona.

One was while deep in the Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya. That night, three lionesses and a lion walked into the campsite where he was staying with his wife, Mona, and a group of researchers. This was in the early 1990s, when Koehler had been invited to address issues with lions attacking the Maasai’s herds of cattle and goats, as well as to work with graduate students while developing a master’s in wildlife program at Moi University. Mona, a registered nurse with a background in public health, was helping establish their medical program.

Back then, before DNA analysis, he says the only way they could distinguish lions was by recording the unique pattern of whisker spots, which are as unique as an individual’s fingerprint. That night, he looked up and saw rather than heard the lions in their campsite. Cats—even the big ones—have a feline way of moving without making a sound. The pride was only 30 or 40 yards away, and all that stood between them was the equivalent of a thin mosquito net.

“Then the lion roared, and it was so loud it shook the ground beneath us,” says Mona.

To better understand big cats, Gary and Mona (pictured here) raised Kamir, a bobcat.

Another encounter, also with Mona, was while working in the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness in Idaho, where he spent seven years studying bobcats, cougars, and coyotes under Hornocker, many as part of his PhD research at the University of Idaho. Koehler and Mona lived there for four winters. To allow them to study a cat more closely, Hornocker gave them a bobcat kitten to raise, which the couple named Kamir (pronounced the same as the phrase they used to address him so often: “come here”). Koehler says it was during this time that he became fascinated with wildcats and “basically spent the bulk of my remaining career studying them.”

Here, in the same wilderness that Hornocker wrote about in the National Geographic article that caused Koehler to go to Idaho in the first place, he and Mona were just waking in their tent. They were the only people around for miles. Koehler woke up and started to go outside when he stopped dead in his tracks and hissed at Mona to get in the center of the tent. While this tent was made of thicker material than the one in Africa, it was still thin enough that the juvenile cougar could easily get in if it wanted to.

“Now, I don’t get scared until Gary’s scared,” says Mona, sitting across from Koehler. “And that’s when I got so scared, I started shaking.”

Back in their tent, they tried to stay as still as possible as they watched the cougar’s shadow slowly slink around the side of tent and finally away from their campsite. “It was pure curiosity,” Koehler says. “That phrase ‘curiosity killed the cat’ is very true. It can get them in trouble.”

Another encounter, also with Mona, was while working in the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness in Idaho, where he spent seven years studying bobcats, cougars, and coyotes under Hornocker, many as part of his PhD research at the University of Idaho. Koehler and Mona lived there for four winters. To allow them to study a cat more closely, Hornocker gave them a bobcat kitten to raise, which the couple named Kamir (pronounced the same as the phrase they used to address him so often: “come here”). Koehler says it was during this time that he became fascinated with wildcats and “basically spent the bulk of my remaining career studying them.”

Here, in the same wilderness that Hornocker wrote about in the National Geographic article that caused Koehler to go to Idaho in the first place, he and Mona were just waking in their tent. They were the only people around for miles. Koehler woke up and started to go outside when he stopped dead in his tracks and hissed at Mona to get in the center of the tent. While this tent was made of thicker material than the one in Africa, it was still thin enough that the juvenile cougar could easily get in if it wanted to.

“Now, I don’t get scared until Gary’s scared,” says Mona, sitting across from Koehler. “And that’s when I got so scared, I started shaking.”

Back in their tent, they tried to stay as still as possible as they watched the cougar’s shadow slowly slink around the side of tent and finally away from their campsite. “It was pure curiosity,” Koehler says. “That phrase ‘curiosity killed the cat’ is very true. It can get them in trouble.”

It’s not surprising that a man who spent 30 years tracking and traipsing into the dens of many of the world’s largest land predators would have his fair share of heart-stopping moments. After a career—and retirement—spent in some of the most remote places on the planet, he can spot tracks on the ground the way a good copyeditor can spot an errant comma. Mona mentions how they hike in the nearby Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest, and Koehler will casually mention that a cougar may be near. In the snow, he can often tell when the tracks are fresh—and always which critter they belong to.

And while Hornocker and his article launched so much of that knowledge and those experiences, among the things Koehler is most grateful to his mentor for these days is pushing him to publish research that helps protect wildlife and to provide experiences similar to those he gave Koehler.

Today, a search for Koehler on Google Scholar brings up 644 publications that he has co-authored or been cited in on topics ranging from harvest management of cougars, which has to do with how many cougars hunters are allowed to kill in a season, to his first, co-authored with Hornocker, which studied the effects of fire on pine marten habitats in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness that spans Idaho and Montana.

KOEHLER CAN OFTEN TELL

WHEN THE TRACKS ARE

FRESH—AND ALWAYS

WHICH CRITTER THEY

BELONG TO.

It’s not surprising that a man who spent 30 years tracking and traipsing into the dens of many of the world’s largest land predators would have his fair share of heart-stopping moments. After a career—and retirement—spent in some of the most remote places on the planet, he can spot tracks on the ground the way a good copyeditor can spot an errant comma. Mona mentions how they hike in the nearby Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest, and Koehler will casually mention that a cougar may be near. In the snow, he can often tell when the tracks are fresh—and always which critter they belong to.

KOEHLER CAN OFTEN TELL WHEN THE TRACKS ARE FRESH—AND ALWAYS WHICH CRITTER THEY BELONG TO.

And while Hornocker and his article launched so much of that knowledge and those experiences, among the things Koehler is most grateful to his mentor for these days is pushing him to publish research that helps protect wildlife and to provide experiences similar to those he gave Koehler.

Today, a search for Koehler on Google Scholar brings up 644 publications that he has co-authored or been cited in on topics ranging from harvest management of cougars, which has to do with how many cougars hunters are allowed to kill in a season, to his first, co-authored with Hornocker, which studied the effects of fire on pine marten habitats in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness that spans Idaho and Montana.

Perhaps the biggest finding from his research is that hunting cougars, which is framed as necessary to keep people and their property safe, often puts both at higher risk.

“We’ve found that there’s just not a chaotic bunch of cats moving on the landscape,” he says. “There are territories maintained by older male cats, who influence adolescent male cats, which are more aggressive and more likely to test their boundaries. Just like human teenagers.”

Here’s how Koehler describes it: When a state or wildlife agency says hunters are allowed to kill 10% of a cat population, they often don’t specify which 10%, allowing hunters—especially trophy hunters—to target the biggest cats. This can wildly disrupt the “law and order” arrangement of a cougar’s social organization because those biggest cats are often the dominant cats that not only know where to hunt on that territory but also how to keep all the other surrounding cats in line.

“We’ve demonstrated through our research that when you have a high harvest rate or high kill rate and take all the males out, what you’re doing is taking away all those ‘No Trespassing’ signs on those territories,” Koehler says.

The young males who move in initially create more chaos because the structure has collapsed and they’re vying for territory. It’s not unlike what happens in a corporate or business setting when there’s a major leadership change. People start vying for more power or better titles and pay grades. Typically, there’s less physical carnage in those situations, but with big cats, farm animals such as chickens and llamas can be put at risk while the not fully developed male cats fight for boundaries and search out the best hunting grounds.

“THERE ARE TERRITORIES MAINTAINED BY OLDER MALE CATS, WHO INFLUENCE ADOLESCENT MALE CATS.”

Perhaps the biggest finding from his research is that hunting cougars, which is framed as necessary to keep people and their property safe, often puts both at higher risk.

“We’ve found that there’s just not a chaotic bunch of cats moving on the landscape,” he says. “There are territories maintained by older male cats, who influence adolescent male cats, which are more aggressive and more likely to test their boundaries. Just like human teenagers.”

“THERE ARE TERRITORIES

MAINTAINED BY OLDER MALE CATS, WHO INFLUENCE ADOLESCENT MALE CATS.”

Here’s how Koehler describes it: When a state or wildlife agency says hunters are allowed to kill 10% of a cat population, they often don’t specify which 10%, allowing hunters—especially trophy hunters—to target the biggest cats. This can wildly disrupt the “law and order” arrangement of a cougar’s social organization because those biggest cats are often the dominant cats that not only know where to hunt on that territory but also how to keep all the other surrounding cats in line.

“We’ve demonstrated through our research that when you have a high harvest rate or high kill rate and take all the males out, what you’re doing is taking away all those ‘No Trespassing’ signs on those territories,” Koehler says.

The young males who move in initially create more chaos because the structure has collapsed and they’re vying for territory. It’s not unlike what happens in a corporate or business setting when there’s a major leadership change. People start vying for more power or better titles and pay grades. Typically, there’s less physical carnage in those situations, but with big cats, farm animals such as chickens and llamas can be put at risk while the not fully developed male cats fight for boundaries and search out the best hunting grounds.

This is among the lessons Koehler introduced to students in the Cle Elum-Roslyn School District as part of Project CAT, short for Cougars and Teaching, which he started in 2000 with the district’s superintendent to get kids excited about research. As part of the eight-year project, students in grades kindergarten through 12th grade were introduced to age-appropriate coursework that taught them everything from the cougar’s food chain and habitats to birth and mortality rates, to actually helping track and tag local big cats.

“We know that for most of us as research scientists affiliated with an organization, it’s harder for us to communicate [with the public],” Koehler says. “And so the kids were our ambassadors for the community, to teach the community what these guys were doing and better understand the biology of these critters.”

It was one of several projects he worked on that involved young people. Matthew Danielson was a sophomore in high school when he joined one of Koehler’s research projects on lynx in the Okanogan County. After graduating from Western Washington University and working for the Department of Natural Resources as a timber sale biologist in Washington’s lynx habitat, he’s now a senior coordinator with Conservation Northwest, helping to coordinate different agencies and biologists and connect them with resources in Chelan and Okanagan counties. At 28, he’s still passionate about lynx, an endangered species that lives in the area he covers, and is currently working on planning a trip this winter to partner with a team of researchers from Home Range Wildlife Research around the forest to find lynx habitats.

“I remember Gary being the ultimate cat biologist,” Danielson says. “He presented a model of what it means to be a research biologist. I didn’t end up going that route because I didn’t want to leave my home valley, but his name still pops up on the literature I reference and he’s the one who taught me how the forest ought to be managed for lynx. And I still think it’s really cool that he gave me all this exposure to what my career could be.”

“[KOEHLER] PRESENTED

A MODEL OF WHAT IT

MEANS TO BE A RESEARCH

BIOLOGIST.”

This is among the lessons Koehler introduced to students in the Cle Elum-Roslyn School District as part of Project CAT, short for Cougars and Teaching, which he started in 2000 with the district’s superintendent to get kids excited about research. As part of the eight-year project, students in grades kindergarten through 12th grade were introduced to age-appropriate coursework that taught them everything from the cougar’s food chain and habitats to birth and mortality rates, to actually helping track and tag local big cats.

“We know that for most of us as research scientists affiliated with an organization, it’s harder for us to communicate [with the public],” Koehler says. “And so the kids were our ambassadors for the community, to teach the community what these guys were doing and better understand the biology of these critters.”

“[KOEHLER] PRESENTED A MODEL OF WHAT IT MEANS TO BE A RESEARCH BIOLOGIST.”

It was one of several projects he worked on that involved young people. Matthew Danielson was a sophomore in high school when he joined one of Koehler’s research projects on lynx in the Okanogan County. After graduating from Western Washington University and working for the Department of Natural Resources as a timber sale biologist in Washington’s lynx habitat, he’s now a senior coordinator with Conservation Northwest, helping to coordinate different agencies and biologists and connect them with resources in Chelan and Okanagan counties. At 28, he’s still passionate about lynx, an endangered species that lives in the area he covers, and is currently working on planning a trip this winter to partner with a team of researchers from Home Range Wildlife Research around the forest to find lynx habitats.

“I remember Gary being the ultimate cat biologist,” Danielson says. “He presented a model of what it means to be a research biologist. I didn’t end up going that route because I didn’t want to leave my home valley, but his name still pops up on the literature I reference and he’s the one who taught me how the forest ought to be managed for lynx. And I still think it’s really cool that he gave me all this exposure to what my career could be.”

Of all the places he’s been, Koehler says the North Cascades are the most beautiful.

Of all the places he’s been, Koehler says the North Cascades are the most beautiful.

For Koehler, Danielson is part of a legacy of appreciation for the land and animals that has been passed down from Hornocker—as well as men like his father, Mark, who first introduced Koehler to both concepts while fishing rainbow trout in Coal Creek near his childhood home and hunting deer, bear, grouse, and ducks.

As a result, Koehler, like Hornocker before him and Danielson after him, has a deep love and respect for this region. And when asked among all the blank spots on the map he’s been—from the Serengeti to the Himalayas and everything in between—what’s the most beautiful, he responds without hesitation: Here. The North Cascades.

It’s not only the place where he came across the article that launched a career that took him around the world several times over or where he returned to spend the rest of his life sharing with others the beauty of Okanagan country and its inhabitants. It’s where you can still find him and Mona, likely harvesting their garden or hiking the trails in the summer and winter with their dogs. These days, he’s less intentionally seeking out tracks. But Koehler is hopeful that because of his work—and that of so many he’s met along the way—the enigmatic predators that captured and continue to hold his imagination are safer and better understood.

For Koehler, Danielson is part of a legacy of appreciation for the land and animals that has been passed down from Hornocker—as well as men like his father, Mark, who first introduced Koehler to both concepts while fishing rainbow trout in Coal Creek near his childhood home and hunting deer, bear, grouse, and ducks.

As a result, Koehler, like Hornocker before him and Danielson after him, has a deep love and respect for this region. And when asked among all the blank spots on the map he’s been—from the Serengeti to the Himalayas and everything in between—what’s the most beautiful, he responds without hesitation: Here. The North Cascades.

It’s not only the place where he came across the article that launched a career that took him around the world several times over or where he returned to spend the rest of his life sharing with others the beauty of Okanagan country and its inhabitants. It’s where you can still find him and Mona, likely harvesting their garden or hiking the trails in the summer and winter with their dogs. These days, he’s less intentionally seeking out tracks. But Koehler is hopeful that because of his work—and that of so many he’s met along the way—the enigmatic predators that captured and continue to hold his imagination are safer and better understood.

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

Located near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, the Vancouver Land Bridge merges rivers, land, people, and trade.