A Confluence of Peregrinations and Prayers

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

For Julie Pham, author of Their War and CEO of CuriosityBased, home is about the people, and being curious is an essential part of understanding them—and yourself.

BY LAURA J. COLE | September 29, 2023

You have to understand,

that no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the land.

Julie Pham shares that excerpt from Warsan Shire’s poem, “Home,” as part of a presentation she gives for Humanities Washington titled, “Hidden Histories: The South Vietnamese Side of the Vietnam War.” She’s given the presentation across the state, as far west as her hometown of Seattle and as far east as Clarkston, which lies along the Idaho border. The session I attended was April 6 at the Clark County Historical Museum in Vancouver, Washington, and included a handful of American Vietnam veterans, a librarian from nearby Washington State University Vancouver, and members of the museum.

“I think about that line all the time,” says Pham, two months later at her home in Newcastle, Washington, where she first moved as a teenager with her family and later returned to help care for her aging parents. “In the Vietnamese community, it’s very common to be like, ‘How did you get here? Were you in the wave that got to go on the helicopter? Or did you come by boat? Or were you sponsored?’ It’s kind of constantly trying to understand how you got here.”

Those questions refer to the more than 125,000 Vietnamese refugees who fled to the United States in 1975, with more than 800,000 later leaving the country by boat. Their flight—and when and how it occurred—is often a pivotal moment in the lives of Vietnam refugees.

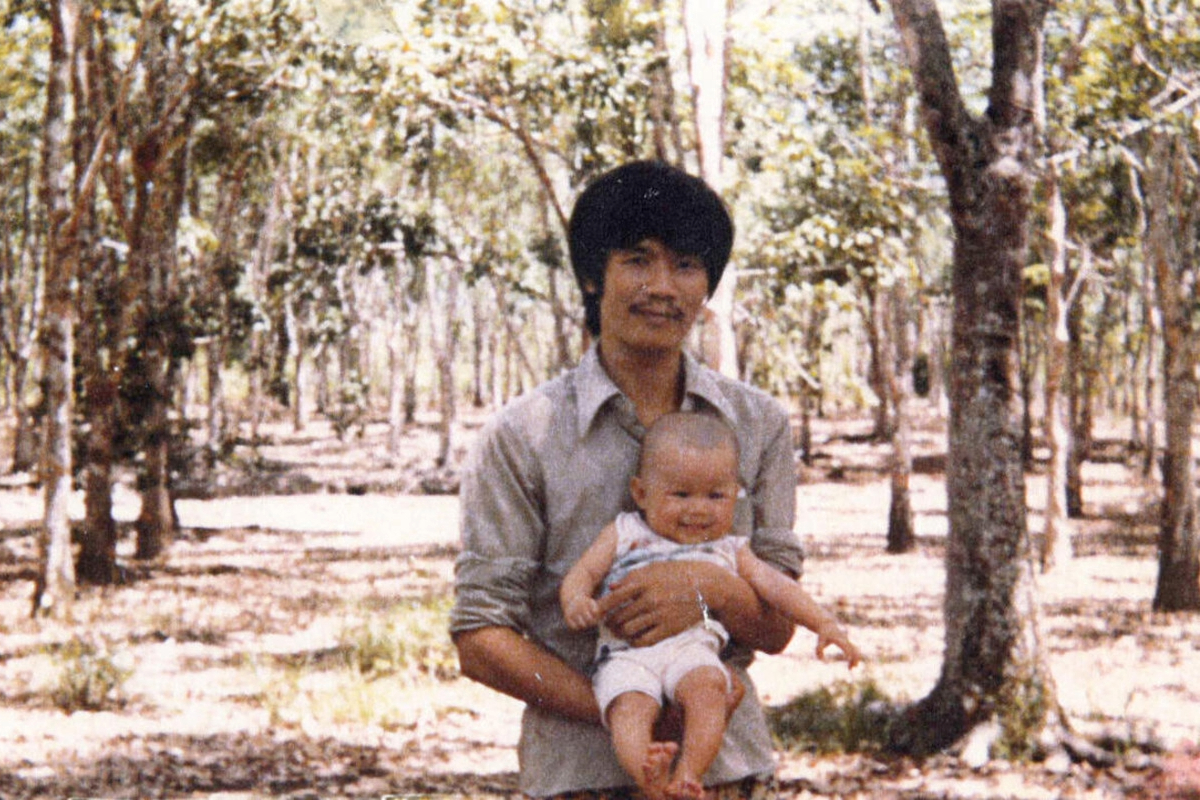

Pham was only 2 months old when she escaped communist Vietnam with her parents by boat. Her father, Kim, was an officer in South Vietnam’s navy during the war. After the Fall of Saigon, he was moved to a re-education camp, where he stayed for three years until being released.

“Because I was afraid of being sent back, I found a way to pay for passage on a boat to escape,” Kim wrote in an article published by Crosscut Media in 2017. “I fled from Vietnam in 1979 with you [Julie] and your mother. We were the first ones in our family to leave.”

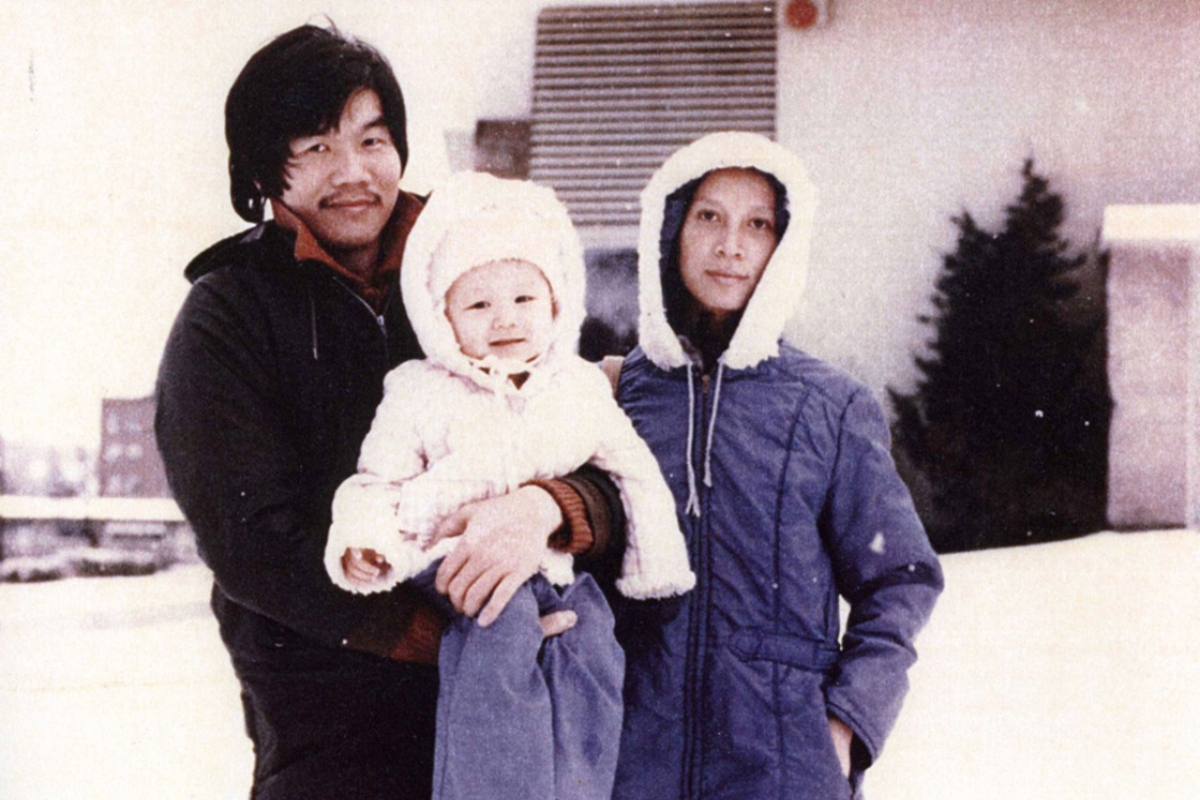

The trio would spend three days and nights on a boat and another five months at a refugee camp in Indonesia before arriving in Seattle, where Pham’s two brothers would later be born.

“We were the lucky ones,” she says. “A week later, my other family members were on a boat that was caught. I actually don’t think I really truly appreciated the risk until hearing all these other stories about the boat people experience. People would get caught and try again because they were determined to get out of there.”

That act of curiosity in wanting to understand others’ experiences and journeys and stories has been a key part of Pham’s own. It has been a driving force in many of her life’s defining moments, including studying history in college, interviewing former military members from the South Vietnamese army, pursuing and leaving academia, and even starting her own consulting practice that helps others foster curiosity in the workplace.

“We were the lucky ones. … People would get caught and try again because they were determined to get out of [Vietnam].”

You have to understand,

that no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the land.

Julie Pham shares that excerpt from Warsan Shire’s poem, “Home,” as part of a presentation she gives for Humanities Washington titled, “Hidden Histories: The South Vietnamese Side of the Vietnam War.” She’s given the presentation across the state, as far west as her hometown of Seattle and as far east as Clarkston, which lies along the Idaho border. The session I attended was April 6 at the Clark County Historical Museum in Vancouver, Washington, and included a handful of American Vietnam veterans, a librarian from nearby Washington State University Vancouver, and members of the museum.

“I think about that line all the time,” says Pham, two months later at her home in Newcastle, Washington, where she first moved as a teenager with her family and later returned to help care for her aging parents. “In the Vietnamese community, it’s very common to be like, ‘How did you get here? Were you in the wave that got to go on the helicopter? Or did you come by boat? Or were you sponsored?’ It’s kind of constantly trying to understand how you got here.”

Those questions refer to the more than 125,000 Vietnamese refugees who fled to the United States in 1975, with more than 800,000 later leaving the country by boat. Their flight—and when and how it occurred—is often a pivotal moment in the lives of Vietnam refugees.

“We were the lucky ones. … People would get caught and try again because they were determined to get out of [Vietnam].”

Pham was only 2 months old when she escaped communist Vietnam with her parents by boat. Her father, Kim, was an officer in South Vietnam’s navy during the war. After the Fall of Saigon, he was moved to a re-education camp, where he stayed for three years until being released.

“Because I was afraid of being sent back, I found a way to pay for passage on a boat to escape,” Kim wrote in an article published by Crosscut Media in 2017. “I fled from Vietnam in 1979 with you [Julie] and your mother. We were the first ones in our family to leave.”

The trio would spend three days and nights on a boat and another five months at a refugee camp in Indonesia before arriving in Seattle, where Pham’s two brothers would later be born.

“We were the lucky ones,” she says. “A week later, my other family members were on a boat that was caught. I actually don’t think I really truly appreciated the risk until hearing all these other stories about the boat people experience. People would get caught and try again because they were determined to get out of there.”

That act of curiosity in wanting to understand others’ experiences and journeys and stories has been a key part of Pham’s own. It has been a driving force in many of her life’s defining moments, including studying history in college, interviewing former military members from the South Vietnamese army, pursuing and leaving academia, and even starting her own consulting practice that helps others foster curiosity in the workplace.

The Pride of Community

To understand Pham, you must first understand where she came from.

Growing up, she says her family moved around a lot. They lived in Tacoma, Federal Way, and Auburn, before moving into the house in Newcastle where she lives today with her brothers. In the ’90s, when Pham was in middle and high school, Asian Americans represented 10% of the population in neighborhoods including Bellevue, Kent, and far north Seattle. Today, people of Asian descent make up roughly 6% of the total US population, but 21% of King County’s population, making it one of the largest Asian American populations in the nation behind Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco.

“I think that that has helped me feel at home,” Pham says. “If I grew up in a place where there wasn’t such a large Asian community or diversity, I don’t know how that would have impacted me. In school and in the community, I got to see my food and people not just represented but celebrated, and all of that has contributed to my worldview—and my sense of pride.”

In 1975, Washington became the first state to welcome Vietnamese refugees after the Fall of Saigon. By the time the Phams made it to the US in the late ’70s, Seattle had a built-in community of Vietnamese refugees who shared her parent’s language and experiences. But it could have been very different.

“Our sponsor was actually in Florida,” she recalls. “We spent a weekend walking around before my dad said, ‘We can’t live here. I want to go back to Seattle.’ So he borrowed money for plane tickets and we flew back here. It’s where we’ve made our life ever since.”

After settling in Seattle, her dad, Kim, became an engineer to support his family, but Pham says he was always an “artist-dreamer at heart.” And when he saw his best friend working at Ngoui Viet—the first, oldest, and largest daily newspaper published in Vietnamese outside of Vietnam, he decided he wanted to start a newspaper of his own. In 1986, they founded Nguoi Viet Tay Bac, or Vietnamese People of the Northwest, which would become the longest-running Vietnamese language newspaper in the Pacific Northwest.

“In the early years, the newspaper office doubled as a print shop,” Pham wrote in an article titled Passing on the Entrepreneurial Spirit. “We were one of the few places Vietnamese could go to for their wedding invitations and business cards since we could typeset in Vietnamese. Eventually, income from advertising increased and my parents made enough to send three kids through college.”

While her dad was the face of the paper, her mom, Hang, whom Pham describes as practical, was the business side. She ensured the paper made money.

The newspaper office in Rainier Valley became their anchor, and she learned a lot watching them run the newspaper, including the courage to take risks.

“My earliest memories are with the newspaper,” Pham says, recalling the smell of ink, visiting advertisers with her parents, and classmates coming up to tell her their parents read the paper. “It was such an important part of our identity, and there was never any doubt or trying to hide it. It instilled that being a refugee is something to be proud of. Even now when I introduce myself, I still include that my parents started a newspaper.”

After high school, Pham moved to the Bay area to attend the University of California – Berkeley with the original intention of going into business law, but that all changed her first semester.

“I just fell in love with history,” she says. “It sits right at the intersection of social sciences, where we’re always looking for truth, and the humanities, where we know there’s no such thing as truth because everyone has a different story.”

Pham laughs now when thinking about how she convinced her parents to send her away to college when “there’s a perfectly good school here,” referring to the University of Washington, where she could have majored in history. But Berkeley allowed her to deepen her practice of curiosity by listening to—and sharing—the often-untold truths that can complicate unified narratives.

“In school and in the community, I got to see my food and people not just represented but celebrated, and all of that has contributed to my worldview—and my sense of pride.”

The Pride of Community

To understand Pham, you must first understand where she came from.

Growing up, she says her family moved around a lot. They lived in Tacoma, Federal Way, and Auburn, before moving into the house in Newcastle where she lives today with her brothers. In the ’90s, when Pham was in middle and high school, Asian Americans represented 10% of the population in neighborhoods including Bellevue, Kent, and far north Seattle. Today, people of Asian descent make up roughly 6% of the total US population, but 21% of King County’s population, making it one of the largest Asian American populations in the nation behind Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco.

“I think that that has helped me feel at home,” Pham says. “If I grew up in a place where there wasn’t such a large Asian community or diversity, I don’t know how that would have impacted me. In school and in the community, I got to see my food and people not just represented but celebrated, and all of that has contributed to my worldview—and my sense of pride.”

In 1975, Washington became the first state to welcome Vietnamese refugees after the Fall of Saigon. By the time the Phams made it to the US in the late ’70s, Seattle had a built-in community of Vietnamese refugees who shared her parent’s language and experiences. But it could have been very different.

“Our sponsor was actually in Florida,” she recalls. “We spent a weekend walking around before my dad said, ‘We can’t live here. I want to go back to Seattle.’ So he borrowed money for plane tickets and we flew back here. It’s where we’ve made our life ever since.”

“In school and in the community, I got to see my food and people not just represented but celebrated, and all of that has contributed to my worldview—and my sense of pride.”

After settling in Seattle, her dad, Kim, became an engineer to support his family, but Pham says he was always an “artist-dreamer at heart.” And when he saw his best friend working at Ngoui Viet—the first, oldest, and largest daily newspaper published in Vietnamese outside of Vietnam, he decided he wanted to start a newspaper of his own. In 1986, they founded Nguoi Viet Tay Bac, or Vietnamese People of the Northwest, which would become the longest-running Vietnamese language newspaper in the Pacific Northwest.

“In the early years, the newspaper office doubled as a print shop,” Pham wrote in an article titled Passing on the Entrepreneurial Spirit. “We were one of the few places Vietnamese could go to for their wedding invitations and business cards since we could typeset in Vietnamese. Eventually, income from advertising increased and my parents made enough to send three kids through college.”

While her dad was the face of the paper, her mom, Hang, whom Pham describes as practical, was the business side. She ensured the paper made money.

The newspaper office in Rainier Valley became their anchor, and she learned a lot watching them run the newspaper, including the courage to take risks.

“My earliest memories are with the newspaper,” Pham says, recalling the smell of ink, visiting advertisers with her parents, and classmates coming up to tell her their parents read the paper. “It was such an important part of our identity, and there was never any doubt or trying to hide it. It instilled that being a refugee is something to be proud of. Even now when I introduce myself, I still include that my parents started a newspaper.”

After high school, Pham moved to the Bay area to attend the University of California – Berkeley with the original intention of going into business law, but that all changed her first semester.

“I just fell in love with history,” she says. “It sits right at the intersection of social sciences, where we’re always looking for truth, and the humanities, where we know there’s no such thing as truth because everyone has a different story.”

Pham laughs now when thinking about how she convinced her parents to send her away to college when “there’s a perfectly good school here,” referring to the University of Washington, where she could have majored in history. But Berkeley allowed her to deepen her practice of curiosity by listening to—and sharing—the often-untold truths that can complicate unified narratives.

Pham didn’t know way back in college that a simple assignment for a seminar would bloom into a research project that has informed everything she has done since.

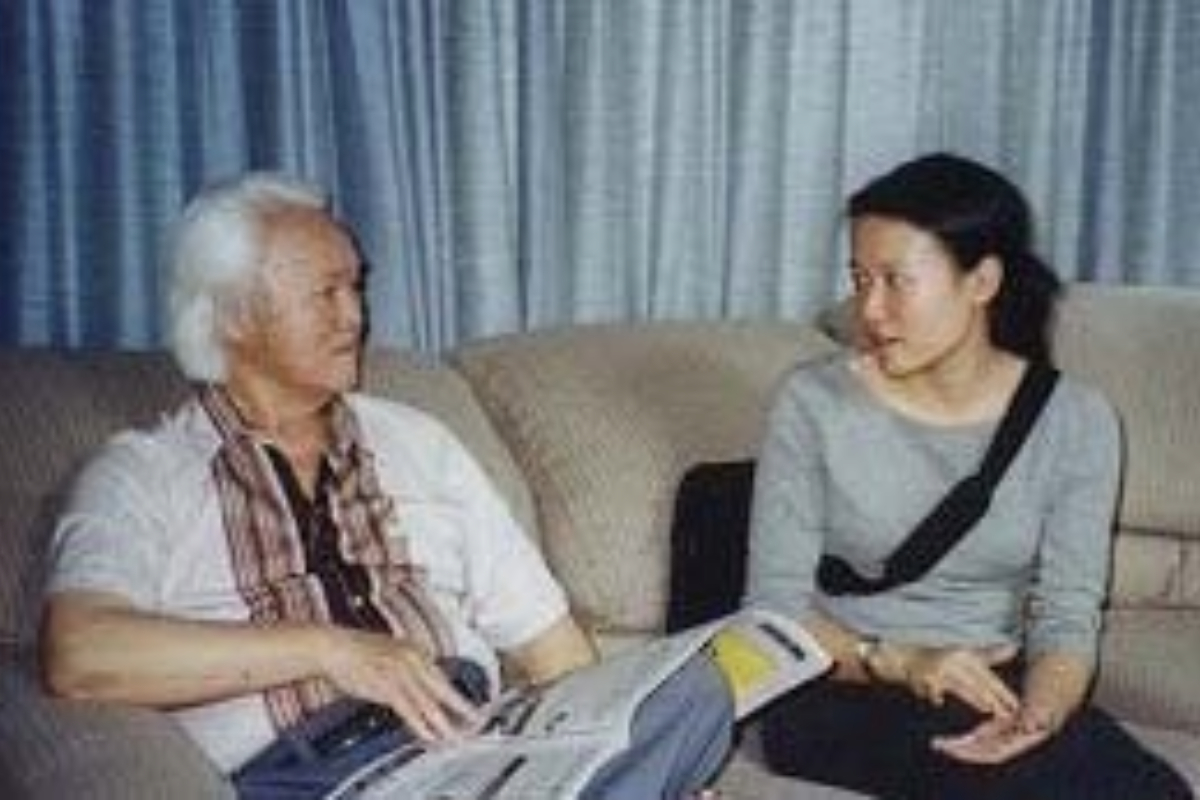

During her sophomore year, Pham was given an assignment that led to a conversation with her dad about depictions of the Vietnam War, particularly how members of the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF)—people like him—were portrayed. Their stories were often misrepresented or left out entirely of the overarching narrative. Intrigued, Pham decided to interview 10 of them for a paper.

The paper became her honors undergraduate thesis at Berkeley, where she graduated in 2001. She ended up interviewing 40 former RVNAF officers, ranging in age and when they fled Vietnam. That thesis is now the book Their War: The Perspectives of the South Vietnamese Military in the Words of Veteran-Emigres and serves as the foundation of the conversations Pham leads for Humanities Washington (HW).

When asked what stands out to her over 20 years later from that initial research, Pham mentions the following quote from Hung Pham, a second wave immigrant who was a cadet officer when Saigon fell and who is unrelated to Julie.

“In my dreams, I can speak English well and very persuasively. I tell Americans a story, tell them about my perception, my view about the war and tell them why communism is not good for the country and communism is why the South Vietnamese people had to flee Vietnam in 1975 and that is why we are here now.”

Pham used the quote to conclude her book—and continues to use it to close her talks with HW. “I want people to remember this and what people could do if they could tell their own story,” she says. “I felt a great sense of responsibility even though at the time I didn’t speak Vietnamese—I was speaking mostly in English with some Vietlish.”

That responsibility comes from telling stories for people who had never shared their stories or couldn’t because of language barriers. Pham was able to earn their trust largely because of her connection to her parents’ newspaper.

That responsibility also comes from sharing the stories of people whose side of the war was largely missing from the historical narrative and who have had shame and guilt thrust upon their stories, even when they often felt neither. Major American postwar films such as Full Metal Jacket, Apocalypse Now, and Good Morning, Vietnam, represented both US veterans and the People’s Army of Vietnam veterans as making the ultimate sacrifice for freedom and the RVNAF—the men she was interviewing—as sidekicks or subordinates to the Americans who simply didn’t want their freedom badly enough.

Her thesis, book, and HW presentation are about sharing a story and perspective that still isn’t told very widely. In telling their stories, she shares critical context, including that more than half of the men she interviewed were part of Operation Passage to Freedom, when nearly one million Vietnamese, mostly Catholic, moved from north to south Vietnam to escape communism. In Their War, she shares that: “When the first American troops arrived in 1965, many Vietnamese had been fighting for up to 15 years. By 1969, there were 875,833 men in the RVNAF—the largest troops on either side of the war. … There was at least one RVNAF member in every South Vietnamese household.”

Like their American counterparts, many of them were also teenagers when they joined the military. But across the board, they “do not remember themselves as mercenaries in a proxy war, or as subordinates.”

Instead, what they remember is the pride they have in being part of it.

“The first time I spoke in Vancouver, Washington, there were a bunch of Vietnamese who came,” she says. “They shared their stories of coming over or how their parents met. There was just so much pride. Even for people in their 50s, it’s like, this is part of my identity. … What I tried to do with the book and in my talks is not to glorify the South Vietnamese, but to allow us to look at other perspectives of the war beyond shame and guilt [which is often the American veterans’ experience].”

“What I tried to do with the book and in my talks is not to glorify the South Vietnamese, but to allow us to look at other perspectives of the war.”

Pham didn’t know way back in college that a simple assignment for a seminar would bloom into a research project that has informed everything she has done since.

During her sophomore year, Pham was given an assignment that led to a conversation with her dad about depictions of the Vietnam War, particularly how members of the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF)—people like him—were portrayed. Their stories were often misrepresented or left out entirely of the overarching narrative. Intrigued, Pham decided to interview 10 of them for a paper.

The paper became her honors undergraduate thesis at Berkeley, where she graduated in 2001. She ended up interviewing 40 former RVNAF officers, ranging in age and when they fled Vietnam. That thesis is now the book Their War: The Perspectives of the South Vietnamese Military in the Words of Veteran-Emigres and serves as the foundation of the conversations Pham leads for Humanities Washington (HW).

When asked what stands out to her over 20 years later from that initial research, Pham mentions the following quote from Hung Pham, a second wave immigrant who was a cadet officer when Saigon fell and who is unrelated to Julie.

“In my dreams, I can speak English well and very persuasively. I tell Americans a story, tell them about my perception, my view about the war and tell them why communism is not good for the country and communism is why the South Vietnamese people had to flee Vietnam in 1975 and that is why we are here now.”

Pham used the quote to conclude her book—and continues to use it to close her talks with HW. “I want people to remember this and what people could do if they could tell their own story,” she says. “I felt a great sense of responsibility even though at the time I didn’t speak Vietnamese—I was speaking mostly in English with some Vietlish.”

“What I tried to do with the book and in my talks is not to glorify the South Vietnamese, but to allow us to look at other perspectives of the war.”

That responsibility comes from telling stories for people who had never shared their stories or couldn’t because of language barriers. Pham was able to earn their trust largely because of her connection to her parents’ newspaper.

That responsibility also comes from sharing the stories of people whose side of the war was largely missing from the historical narrative and who have had shame and guilt thrust upon their stories, even when they often felt neither. Major American postwar films such as Full Metal Jacket, Apocalypse Now, and Good Morning, Vietnam, represented both US veterans and the People’s Army of Vietnam veterans as making the ultimate sacrifice for freedom and the RVNAF—the men she was interviewing—as sidekicks or subordinates to the Americans who simply didn’t want their freedom badly enough.

Her thesis, book, and HW presentation are about sharing a story and perspective that still isn’t told very widely. In telling their stories, she shares critical context, including that more than half of the men she interviewed were part of Operation Passage to Freedom, when nearly one million Vietnamese, mostly Catholic, moved from north to south Vietnam to escape communism. In Their War, she shares that: “When the first American troops arrived in 1965, many Vietnamese had been fighting for up to 15 years. By 1969, there were 875,833 men in the RVNAF—the largest troops on either side of the war. … There was at least one RVNAF member in every South Vietnamese household.”

Like their American counterparts, many of them were also teenagers when they joined the military. But across the board, they “do not remember themselves as mercenaries in a proxy war, or as subordinates.”

Instead, what they remember is the pride they have in being part of it.

“The first time I spoke in Vancouver, Washington, there were a bunch of Vietnamese who came,” she says. “They shared their stories of coming over or how their parents met. There was just so much pride. Even for people in their 50s, it’s like, this is part of my identity. … What I tried to do with the book and in my talks is not to glorify the South Vietnamese, but to allow us to look at other perspectives of the war beyond shame and guilt [which is often the American veterans’ experience].”

When asked what defines her identity, Pham responds: optimism, which she attributes to being Vietnamese; courage, which she says she learned through osmosis from watching her father; and curiosity, which she has discovered is a practice, like meditation, rather than a characteristic or personality trait.

All three explain the major decisions that have defined her life, which include learning Vietnamese, deciding to leave academia right as she was earning her doctorate, and starting over again nearly a decade later when she walked away from “the best job I’ve ever had” to create her own business.

After graduating from Berkeley, Pham spent a summer in Madison, Wisconsin, studying the Vietnamese language at a Southeast Asian language bootcamp, before spending a year in England, where she began working on her MPhil at the University of Cambridge. While studying, she bounced between England, France, Germany, Vietnam, and California.

“I wasn’t in any place for longer than 15 months in my 20s,” she says.

Though her parents would never return to Vietnam, Pham credits her country of origin with teaching her two of the three main elements she’s identified as critical for the practice of curiosity: clear communication and self-awareness.

“I discovered this inner steel, this toughness, and I really grew up in Vietnam,” Pham says. “I learned about money, how to be independent, and how to communicate clearly. The Pacific Northwest is pretty famous for its passive language and people speaking indirectly, but speaking a second language, I had to learn to be direct, especially while negotiating in the markets.”

It was there in Hanoi that she also learned to listen to herself.

“I remember I was working on my dissertation, and I was just like I don’t want to do this. I don’t want to stay in academia,” she recalls. “I don’t actually know what’s next, but I know that I don’t want to do this.”

Her entire focus until that point had been continuing on the path of grants and fellowships and professorships. It’s what her friends were doing, and what she knew. Despite all of that, she listened to herself, and in 2008—halfway through the Great Recession—she returned to Seattle with no plan or job, thinking she’d work for the family newspaper for a bit.

“I remember that summer is when things started to crash,” she says. “Newspaper offices were just beginning to start closing. A year later, we saw the closure of the Seattle [Post-Intelligencer]. I had just earned my Cambridge PhD and was working at my parents’ newspaper making $15,000 a year. It was hard. It was so, so hard.”

It took time and persistence, but she made it work. She and her brother took out a loan and bought half of the newspaper. She formed a Pacific Northwest coalition for ethnic media that included Spanish, Chinese, American, and Russian newspapers. She landed a job at Washington Technology Industry Association, where she worked as vice president of community engagement for six years.

While working at the latter, the idea for her own business came to her. Pham noticed that the people who were struggling were focused on outcomes and the ones who thriving—who were doing well and actually having fun—were practicing curiosity.

The curiosity was contagious. Pham began writing for herself, exploring her observations as a way to better understand what she wanted and where she wanted to go. At the end of 2020, she created a Substack called CuriosityBased to publish her thoughts, in addition to writing for other publications, and moved back into her childhood home to help take care of her dad, who has since passed. A few months later, she launched CuriosityBased to help business leaders build strong, collaborative, curious teams.

One concept that kept coming up again and again in her writing and in working with business leaders was respect. What does it look like? How does it change from person to person, culture to culture? How do we get—and how do give it?

“I’ve learned most of the time, we’re interested in being heard but not hearing,” Pham says. “But when I talk about curiosity, it means being actually open to the fact that we may change. If you want other people to listen to you, you have to listen to them. If you want other people to learn from you, you have to be willing to learn from them. And if you want people to give you grace, you have to give them grace—and we all need to give ourselves more grace.”

She turned that realization into a book, 7 Forms of Respect: A Guide to Transforming Your Communication and Relationships at Work. Published in May 2022, the book outlines the types of respect people value: Procedure, Punctuality, Information, Candor, Consideration, Acknowledgement, and Attention.

“It’s not about getting all seven,” Pham says. “That’s perfectionist thinking. It’s about getting in touch with yourself. Because the practice of curiosity comes down to three elements: self-awareness, relationship building, and clear communication. And I hope the book gives people a framework to say ‘these are forms of respect I prioritize. What are yours?’ ”

During her presentation at Clark County Historical Museum in Vancouver, Pham puts this knowledge into practice. She doesn’t just share the quotes from the men she interviewed who have different lived experiences from everyone else in the room. She invites audience members to come up and read them, imagining others’ stories as their own. Then she asks the American veterans in the room to share their experiences. Then for all of us to ask questions, to share, to listen, to be curious.

It feels intimate and inviting and personal. Just like Pham.

“The practice of curiosity comes down to three elements: self-awareness, relationship building, and clear communication.”

When asked what defines her identity, Pham responds: optimism, which she attributes to being Vietnamese; courage, which she says she learned through osmosis from watching her father; and curiosity, which she has discovered is a practice, like meditation, rather than a characteristic or personality trait.

All three explain the major decisions that have defined her life, which include learning Vietnamese, deciding to leave academia right as she was earning her doctorate, and starting over again nearly a decade later when she walked away from “the best job I’ve ever had” to create her own business.

After graduating from Berkeley, Pham spent a summer in Madison, Wisconsin, studying the Vietnamese language at a Southeast Asian language bootcamp, before spending a year in England, where she began working on her MPhil at the University of Cambridge. While studying, she bounced between England, France, Germany, Vietnam, and California.

“I wasn’t in any place for longer than 15 months in my 20s,” she says.

Though her parents would never return to Vietnam, Pham credits her country of origin with teaching her two of the three main elements she’s identified as critical for the practice of curiosity: clear communication and self-awareness.

“I discovered this inner steel, this toughness, and I really grew up in Vietnam,” Pham says. “I learned about money, how to be independent, and how to communicate clearly. The Pacific Northwest is pretty famous for its passive language and people speaking indirectly, but speaking a second language, I had to learn to be direct, especially while negotiating in the markets.”

It was there in Hanoi that she also learned to listen to herself.

“I remember I was working on my dissertation, and I was just like I don’t want to do this. I don’t want to stay in academia,” she recalls. “I don’t actually know what’s next, but I know that I don’t want to do this.”

Her entire focus until that point had been continuing on the path of grants and fellowships and professorships. It’s what her friends were doing, and what she knew. Despite all of that, she listened to herself, and in 2008—halfway through the Great Recession—she returned to Seattle with no plan or job, thinking she’d work for the family newspaper for a bit.

“I remember that summer is when things started to crash,” she says. “Newspaper offices were just beginning to start closing. A year later, we saw the closure of the Seattle [Post-Intelligencer]. I had just earned my Cambridge PhD and was working at my parents’ newspaper making $15,000 a year. It was hard. It was so, so hard.”

It took time and persistence, but she made it work. She and her brother took out a loan and bought half of the newspaper. She formed a Pacific Northwest coalition for ethnic media that included Spanish, Chinese, American, and Russian newspapers. She landed a job at Washington Technology Industry Association, where she worked as vice president of community engagement for six years.

While working at the latter, the idea for her own business came to her. Pham noticed that the people who were struggling were focused on outcomes and the ones who thriving—who were doing well and actually having fun—were practicing curiosity.

“The practice of curiosity comes down to three elements: self-awareness, relationship building, and clear communication.”

The curiosity was contagious. Pham began writing for herself, exploring her observations as a way to better understand what she wanted and where she wanted to go. At the end of 2020, she created a Substack called CuriosityBased to publish her thoughts, in addition to writing for other publications, and moved back into her childhood home to help take care of her dad, who has since passed. A few months later, she launched CuriosityBased to help business leaders build strong, collaborative, curious teams.

One concept that kept coming up again and again in her writing and in working with business leaders was respect. What does it look like? How does it change from person to person, culture to culture? How do we get—and how do give it?

“I’ve learned most of the time, we’re interested in being heard but not hearing,” Pham says. “But when I talk about curiosity, it means being actually open to the fact that we may change. If you want other people to listen to you, you have to listen them. If you want other people to learn from you, you have to be willing to learn from them. And if you want people to give you grace, you have to give them grace—and we all need to give ourselves more grace.”

She turned that realization into a book, 7 Forms of Respect: A Guide to Transforming Your Communication and Relationships at Work. Published in May 2022, the book outlines the types of respect people value: Procedure, Punctuality, Information, Candor, Consideration, Acknowledgement, and Attention.

“It’s not about getting all seven,” Pham says. “That’s perfectionist thinking. It’s about getting in touch with yourself. Because the practice of curiosity comes down to three elements: self-awareness, relationship building, and clear communication. And I hope the book gives people a framework to say ‘these are forms of respect I prioritize. What are yours?’ ”

During her presentation at Clark County Historical Museum in Vancouver, Pham puts this knowledge into practice. She doesn’t just share the quotes from the men she interviewed who have different lived experiences from everyone else in the room. She invites audience members to come up and read them, imagining others’ stories as their own. Then she asks the American veterans in the room to share their experiences. Then for all of us to ask questions, to share, to listen, to be curious.

It feels intimate and inviting and personal. Just like Pham.

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

Located near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, the Vancouver Land Bridge merges rivers, land, people, and trade.