A Confluence of Peregrinations and Prayers

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

HEARING

THE

EARTH

For Michael Mason, a longtime attorney and lobbyist for Pacific Northwest tribes, home is deeply rooted in the land, history, and songs of this region.

BY LAURA J. COLE | PHOTOS BY BILL PURCELL

September 25, 2023

Michael Mason arrived at Fleur de Lis in northeast Portland on a late morning in May, wearing a green and blue long-sleeve Pendleton wool shirt with a sprig of Oregon white oak leaves in his pocket. He handed it to me, saying, “That’s for you. There’s a story there I’ll tell you later.”

He picked the shoot while spending the morning removing invasive Scotch broom—cytisus scoparius, he says in passing—from along the banks of the Quick Sandy River.

“My Scottish ancestors brought the damn things here,” he says, “but the Natives are allergic to it. I’m not, so I remove what I can.”

Indeed, after talking with Mason—an attorney and registered Oregon lobbyist for the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs, Coquille Indian Tribe, and Klamath Tribes—for any length of time, you’ll find most of the plants and rivers and people and regions in the Pacific Northwest have stories. And having lived in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, he knows and delights in sharing many of them.

During our 90-minute conversation over coffee and breakfast, he talks about: his first relative to move to the Pacific Northwest, a homesteader, who arrived in Prineville, Oregon, in 1866, by way of the Oregon Trail from the Colorado mines; about his grandfather, who came to Washington from the Texas Hill Country to work on the Grand Coulee Dam, which he lost a little bit of his pinkie finger in, and never went back (“he had no love of Texas”); about the Chinook, led by Chief Comcomly, who saved the American Exploratory Expedition of 1848 by leading them safely into the Columbia River, “one of the most dangerous river mouths in the hemisphere;” and about “really great Republicans” like Tom McCall, who protected Oregon’s beauty by signing into law one of the best land-use systems in the nation, and Mark O. Hatfield, who helped establish wilderness, wild and scenic rivers, and the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area.

What is true for all of these stories is their connection to the land, something Mason calls an essential part of what it means to be an Oregonian.

“We’re the Eden at the end of the Oregon Trail,” he says. “You gotta kind of deserve all of this beautiful, amazing stuff we’ve been blessed with. A big part of my upbringing was believing that we were the last best hope for the United States, if not the world. We need to protect it.”

As a child, protecting it meant learning to shoot a rifle, even if he wasn’t entirely sure why. All he remembers is being 9, and his grandfather—who grew up on a dairy farm in Winlock, Washington—telling him, his sister, and his brother that he was going to teach them how to shoot. He then grabbed a couple of rifles and took them out to practice their aim on some cans and bottles set along a fence.

“He said, ‘This is really important that you learn how to do this because California is trying to take the Columbia River, and we have to be able to stop them. The only way we’re going to do that is we’re going to have to go down to the Columbia and face them off with our guns,’ ” Mason recalls. “I had no idea what he was talking about. How do you take a river? Later I learned San Diego talked about it, but it was never gonna happen. But people don’t know that. They just know California is huge, and we were gonna form a militia and save our water.”

Oregon white oak is the only native oak north of Eugene, Oregon. It’s scientific name, Quercus garryana, is in honor of Nicholas Garry, secretary and later deputy governor of the Hudson Bay Company.

Photograph by YVC Biology Department / Flickr

Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius) is a native of Europe and North Africa, stretching from Great Britain to the Ural Mountains. The woody shrub was introduced in California in the 1850s and has since become an invasive in the Pacific Northwest.

Illustration by Maria Sibyl Merian / RawPixel

Michael Mason arrived at Fleur de Lis in northeast Portland on a late morning in May, wearing a green and blue long-sleeve Pendleton wool shirt with a sprig of Oregon white oak leaves in his pocket. He handed it to me, saying, “That’s for you. There’s a story there I’ll tell you later.”

He picked the shoot while spending the morning removing invasive Scotch broom—cytisus scoparius, he says in passing—from along the banks of the Quick Sandy River.

“My Scottish ancestors brought the damn things here,” he says, “but the Natives are allergic to it. I’m not, so I remove what I can.”

Indeed, after talking with Mason—an attorney and registered Oregon lobbyist for the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs, Coquille Indian Tribe, and Klamath Tribes—for any length of time, you’ll find most of the plants and rivers and people and regions in the Pacific Northwest have stories. And having lived in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, he knows and delights in sharing many of them.

During our 90-minute conversation over coffee and breakfast, he talks about: his first relative to move to the Pacific Northwest, a homesteader, who arrived in Prineville, Oregon, in 1866, by way of the Oregon Trail from the Colorado mines; about his grandfather, who came to Washington from the Texas Hill Country to work on the Grand Coulee Dam, which he lost a little bit of his pinkie finger in, and never went back (“he had no love of Texas”); about the Chinook, led by Chief Comcomly, who saved the American Exploratory Expedition of 1848 by leading them safely into the Columbia River, “one of the most dangerous river mouths in the hemisphere;” and about “really great Republicans” like Tom McCall, who protected Oregon’s beauty by signing into law one of the best land-use systems in the nation, and Mark O. Hatfield, who helped establish wilderness, wild and scenic rivers, and the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area.

“We’re the Eden at the end of the Oregon Trail. You gotta kind of deserve all of this beautiful, amazing stuff we’ve been blessed with. …

We need to protect it.”

What is true for all of these stories is their connection to the land, something Mason calls an essential part of what it means to be an Oregonian.

“We’re the Eden at the end of the Oregon Trail,” he says. “You gotta kind of deserve all of this beautiful, amazing stuff we’ve been blessed with. A big part of my upbringing was believing that we were the last best hope for the United States, if not the world. We need to protect it.”

As a child, protecting it meant learning to shoot a rifle, even if he wasn’t entirely sure why. All he remembers is being 9, and his grandfather—who grew up on a dairy farm in Winlock, Washington—telling him, his sister, and his brother that he was going to teach them how to shoot. He then grabbed a couple of rifles and took them out to practice their aim on some cans and bottles set along a fence.

“He said, ‘This is really important that you learn how to do this because California is trying to take the Columbia River, and we have to be able to stop them. The only way we’re going to do that is we’re going to have to go down to the Columbia and face them off with our guns,’ ” Mason recalls. “I had no idea what he was talking about. How do you take a river? Later I learned San Diego talked about it, but it was never gonna happen. But people don’t know that. They just know California is huge, and we were gonna form a militia and save our water.”

“When it comes to the government, our tribes should be treated like Fortune 500 corporations. … They actually know what’s going on in this world.”

“When it comes to the government, our tribes should be treated like Fortune 500 corporations. … They actually know what’s going on in this world.”

An Advocate for Native Tribes

As an adult, protecting the PNW is somewhat less literal, but still equally tied to the environment and the people who call it home.

Mason’s life work has been advocating for and defending the tribes who have called this land home for thousands of years—long before Lewis and Clark, long before the first white settlers, and long before his homesteading ancestor in Crook County whom he calls his “Oregon Trail guy.”

“When it comes to the government, our tribes should be treated like Fortune 500 corporations,” Mason says. “Tribes should be up there. They shouldn’t be brown down. They actually know what’s going on in this world. I’m proud of my Oregon Trail guy, but that’s only 1866. The Natives don’t care. ‘We were here for 14,000 years, bud. You’re only scratching the surface.’ ”

When asked what it means to him to call the Pacific Northwest home, he says one of the most fundamental aspects of being a Westerner is existing with the tribes. Not that there hasn’t been conflict or strain for the tribes in that relationship. Part of what drew Mason to his work was the Civil Rights Movement and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s words. When he looked around growing up, the people who were the most oppressed were the Native Americans.

Around the same time he was being inspired by Martin Luther King, Jr.’s words, he recalls watching the police beat up Puyallup members for fishing where they had always fished. This was in Tacoma, Washington, near where he attended high school.

“That really stuck with me,” he says, “because we grew up watching them fish in these same places.” That injustice and a love of the natural beauty of the PNW inspired Mason to want to become a lawyer, specializing in civil rights or environmental law, the latter of which he pursued initially.

While a senior at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, Mason did an internship with the state legislature. One of the senators asked him to research what a proposed supertanker port in Port Angeles would do for his constituents, to which Mason replied, “nothing”: “It would be 12 full-time jobs permanently and maybe 35 or 40 for the construction, but otherwise it was just gonna destroy the environment. One spill and it destroys salmon grounds, orcas, all of it. I said this is nuts. There’s nothing in this for us. Luckily, it never came to fruition,” he says.

The call for defending tribes came partly when he got fired from that same internship. A representative from Camas, Washington, asked him to write a bill banning gillnetting—a type of fishing using a vertical net—on the Columbia River. After talking with the American Friends Service Committee and getting up-to-speed on treaties, he wrote the bill—but did not include the tribes. The rep read the proposed bill, and asked, “Where are the Indians?” Mason responded that because of the treaties, they were protected by the Constitution, unless gillnetting threated the survival of a species or subspecies.

“I realize now, he must have thought I was this 21-year-old lecturing him,” Mason says. “But I really was curious. How could I do that? He asked me if I was going to add them or not, and I said, ‘Well, I believe in the Constitution. How can I put that in there?’ He told me to get out of his office and not to come back.”

That representative ended up rewriting the bill to include tribes in the ban, but the bill didn’t pass. Mason calls it his first exposure to “the hatred on the Columbia River.”

The second part of his call to defend tribes came in law school at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, back, he says, when Stumptown was still considering becoming a city. He took a course called Indian Law, and on the last day of class, the head of the Legal Aid program attended and spoke about the water wars, which Mason was interested in. After class, Mason went and told him he wanted to work for him and learned there was an internship available. He got the job and ended up doing a five-month internship with the Native American Rights Fund in Washington, D.C. That led to working with Legal Aid in Idaho, followed shortly after by a stint working for the solicitor for Indian Affairs in the U.S. Department of the Interior.

“I almost stayed in Oregon, but if I hadn’t gone to Idaho, I wouldn’t have gotten to do some really fun stuff at the interior department,” he says. “That was the most valuable experience for representing tribes because I came to understand how the federal system works. It’s a total bafflement if you’re not in it. It’s got its own kind of fractal work going on that doesn’t have anything to do with the citizenry.”

But he did return to Oregon, in 1992, where he has lived ever since. During his career here—which includes 22 years as chair of the Legal Aid Services of Oregon and several years on the advisory board for the Native American Program of Legal Aid Services of Oregon—he’s worked on a slew of initiatives. Among the ones he’s most proud of are helping set up Spirit Mountain Casino while working as an in-house tribal attorney for the Grand Ronde—and then defeating (alongside a team of lobbyists) the 19 bills that came a year and a half later aimed at reducing or eliminating gambling in Oregon that would have threatened its success.

The other is helping the Coquille tribe in southern Oregon regain their tribal status—a status the government took from them in the 1950s.

After World War II, in an act referred to as a termination of trust relations, the federal government voted to strip Native peoples of federal aid, services, protections, and their reservations as well as protective responsibilities for their lands that were guaranteed to them in 374 treaties that were negotiated and ratified between 1778 and 1871. The first of these termination acts came in 1953, when Congress approved Resolution 108, which directed the government, “as rapidly as possible, to make the Indians within the territorial limits of the United States subject to the same laws and entitled to the same privileges and responsibilities as are applicable to other citizens of the United States, and to end their status as wards of the United States, and to grant them all of the rights and prerogatives pertaining to American citizenship.”

That wording is dubiously misleading. In reality, it took so much more than it gave.

Coinciding with the McCarthy era anti-Communism movement and led by senators Henry Jackson (D-Washington) and Arthur Watkins (R-Utah), a small group persuaded their colleagues to end the federal trust status of tribes, beginning with the Menominee of Wisconsin. Shortly after, on August 13, 1954, President Eisenhower signed into law Public Law 588, which terminated the trust of the Coquille, as well as the Siletz, Grand Ronde, Coos, Lower Umpqua, Siuslaw, and other Oregon tribes.

Termination was a sweeping blow to tribes across the nation that radically changed the lives of many Native peoples. The reversal, referred to as restoration, would take nearly 20 years, beginning with the Menominee Restoration Act in 1973. The second was Siletz Restoration Act, which went into effect in 1977.

For the Coquille, it would take an additional 12 years. On June 28, 1989, Congress once again recognized them as a sovereign nation, with Mason helping to spearhead the legal efforts to pass the Coquille Restoration Act.

“It was a great honor to work with [Representative] Elizabeth Furse [(D-Oregon)] to get that restored, and they got the best restoration act in the West,” Mason says. “They have what’s called federal service areas, where any tribal member who lives there has access to the full range of Bureau of Indian Affairs, Indian Health Services, Housing and Urban Development, as well as the mandatory land into trust provision and the possibility of having reservation lands anywhere in their service area.”

More recently, the Coquille entered an agreement with the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission to co-manage hunting and fishing for Coos, Curry, Douglas, Jackson, and Lane counties.

“It extends to all the counties where they lived in Southern Oregon, even though some were not part of the Coquille territory—that includes Lane County all the way to the crest of the Cascades. Jackson County to the fucking crest of the Cascades. This is an amazing agreement—and it’s unheard of in the United States.

“That’s one thing about Oregon,” Mason continues. “We are willing to try things. There’s a creativity in terms of policy that is just beautiful to see.”

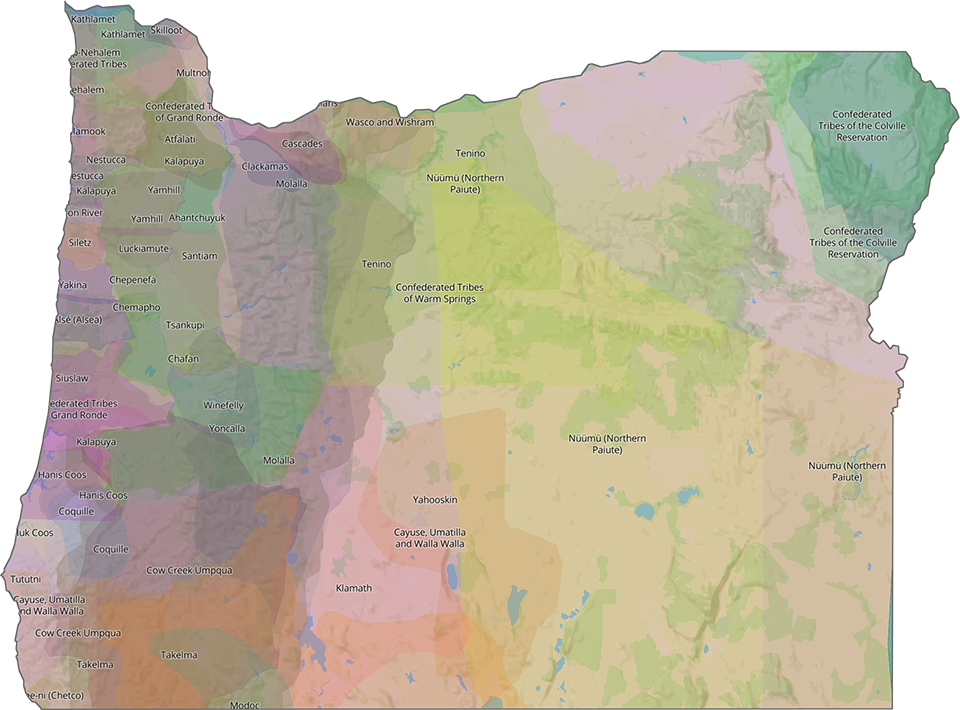

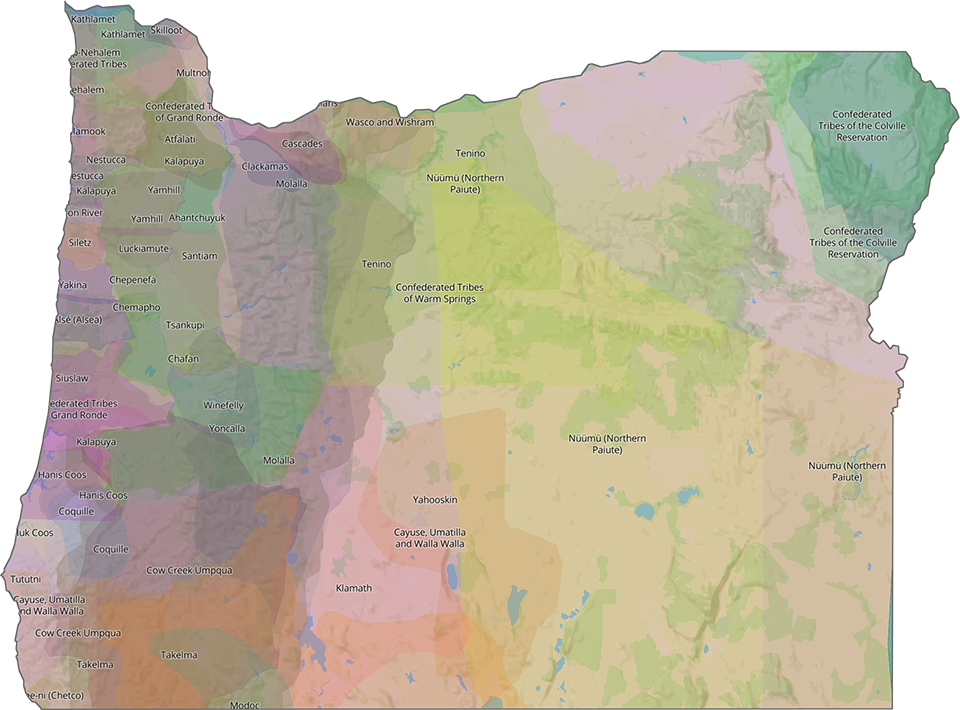

More than 60 tribes inhabited what is now known as Oregon, speaking at least 18 languages across hundreds of villages. Today, Oregon has nine federally recognized tribes, and land acknowledgments have become common practice at meetings, conferences, and symposia.

“That’s one thing about Oregon. We are willing to try things. There’s a creativity in terms of policy that is just beautiful to see.”

Mason has two albums inspired by his love of the Pacific Northwest. The most recent, Seasons of Trouble, was released in September. Both are available for streaming and for purchase at Music Millenium in Portland.

An Advocate for Native Tribes

As an adult, protecting the PNW is somewhat less literal, but still equally tied to the environment and the people who call it home.

Mason’s life work has been advocating for and defending the tribes who have called this land home for thousands of years—long before Lewis and Clark, long before the first white settlers, and long before his homesteading ancestor in Crook County whom he calls his “Oregon Trail guy.”

“When it comes to the government, our tribes should be treated like Fortune 500 corporations,” Mason says. “Tribes should be up there. They shouldn’t be brown down. They actually know what’s going on in this world. I’m proud of my Oregon Trail guy, but that’s only 1866. The Natives don’t care. ‘We were here for 14,000 years, bud. You’re only scratching the surface.’ ”

When asked what it means to him to call the Pacific Northwest home, he says one of the most fundamental aspects of being a Westerner is existing with the tribes. Not that there hasn’t been conflict or strain for the tribes in that relationship. Part of what drew Mason to his work was the Civil Rights Movement and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s words. When he looked around growing up, the people who were the most oppressed were the Native Americans.

Around the same time he was being inspired by Martin Luther King, Jr.’s words, he recalls watching the police beat up Puyallup members for fishing where they had always fished. This was in Tacoma, Washington, near where he attended high school.

“That really stuck with me,” he says, “because we grew up watching them fish in these same places.” That injustice and a love of the natural beauty of the PNW inspired Mason to want to become a lawyer, specializing in civil rights or environmental law, the latter of which he pursued initially.

“That’s one thing about Oregon. We are willing to try things. There’s a creativity in terms of policy that is just beautiful to see.”

While a senior at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, Mason did an internship with the state legislature. One of the senators asked him to research what a proposed supertanker port in Port Angeles would do for his constituents, to which Mason replied, “nothing”: “It would be 12 full-time jobs permanently and maybe 35 or 40 for the construction, but otherwise it was just gonna destroy the environment. One spill and it destroys salmon grounds, orcas, all of it. I said this is nuts. There’s nothing in this for us. Luckily, it never came to fruition,” he says.

The call for defending tribes came partly when he got fired from that same internship. A representative from Camas, Washington, asked him to write a bill banning gillnetting—a type of fishing using a vertical net—on the Columbia River. After talking with the American Friends Service Committee and getting up-to-speed on treaties, he wrote the bill—but did not include the tribes. The rep read the proposed bill, and asked, “Where are the Indians?” Mason responded that because of the treaties, they were protected by the Constitution, unless gillnetting threated the survival of a species or subspecies.

“I realize now, he must have thought I was this 21-year-old lecturing him,” Mason says. “But I really was curious. How could I do that? He asked me if I was going to add them or not, and I said, ‘Well, I believe in the Constitution. How can I put that in there?’ He told me to get out of his office and not to come back.”

That representative ended up rewriting the bill to include tribes in the ban, but the bill didn’t pass. Mason calls it his first exposure to “the hatred on the Columbia River.”

The second part of his call to defend tribes came in law school at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, back, he says, when Stumptown was still considering becoming a city. He took a course called Indian Law, and on the last day of class, the head of the Legal Aid program attended and spoke about the water wars, which Mason was interested in. After class, Mason went and told him he wanted to work for him and learned there was an internship available. He got the job and ended up doing a five-month internship with the Native American Rights Fund in Washington, D.C. That led to working with Legal Aid in Idaho, followed shortly after by a stint working for the solicitor for Indian Affairs in the U.S. Department of the Interior.

“I almost stayed in Oregon, but if I hadn’t gone to Idaho, I wouldn’t have gotten to do some really fun stuff at the interior department,” he says. “That was the most valuable experience for representing tribes because I came to understand how the federal system works. It’s a total bafflement if you’re not in it. It’s got its own kind of fractal work going on that doesn’t have anything to do with the citizenry.”

More than 60 tribes inhabited what is now known as Oregon, speaking at least 18 languages across hundreds of villages. Today, Oregon has nine federally recognized tribes, and land acknowledgments have become common practice at meetings, conferences, and symposia.

But he did return to Oregon, in 1992, where he has lived ever since. During his career here—which includes 22 years as chair of the Legal Aid Services of Oregon and several years on the advisory board for the Native American Program of Legal Aid Services of Oregon—he’s worked on a slew of initiatives. Among the ones he’s most proud of are helping set up Spirit Mountain Casino while working as an in-house tribal attorney for the Grand Ronde—and then defeating (alongside a team of lobbyists) the 19 bills that came a year and a half later aimed at reducing or eliminating gambling in Oregon that would have threatened its success.

The other is helping the Coquille tribe in southern Oregon regain their tribal status—a status the government took from them in the 1950s.

After World War II, in an act referred to as a termination of trust relations, the federal government voted to strip Native peoples of federal aid, services, protections, and their reservations as well as protective responsibilities for their lands that were guaranteed to them in 374 treaties that were negotiated and ratified between 1778 and 1871. The first of these termination acts came in 1953, when Congress approved Resolution 108, which directed the government, “as rapidly as possible, to make the Indians within the territorial limits of the United States subject to the same laws and entitled to the same privileges and responsibilities as are applicable to other citizens of the United States, and to end their status as wards of the United States, and to grant them all of the rights and prerogatives pertaining to American citizenship.”

That wording is dubiously misleading. In reality, it took so much more than it gave.

Coinciding with the McCarthy era anti-Communism movement and led by senators Henry Jackson (D-Washington) and Arthur Watkins (R-Utah), a small group persuaded their colleagues to end the federal trust status of tribes, beginning with the Menominee of Wisconsin. Shortly after, on August 13, 1954, President Eisenhower signed into law Public Law 588, which terminated the trust of the Coquille, as well as the Siletz, Grand Ronde, Coos, Lower Umpqua, Siuslaw, and other Oregon tribes.

Termination was a sweeping blow to tribes across the nation that radically changed the lives of many Native peoples. The reversal, referred to as restoration, would take nearly 20 years, beginning with the Menominee Restoration Act in 1973. The second was Siletz Restoration Act, which went into effect in 1977.

For the Coquille, it would take an additional 12 years. On June 28, 1989, Congress once again recognized them as a sovereign nation, with Mason helping to spearhead the legal efforts to pass the Coquille Restoration Act.

“It was a great honor to work with [Representative] Elizabeth Furse [(D-Oregon)] to get that restored, and they got the best restoration act in the West,” Mason says. “They have what’s called federal service areas, where any tribal member who lives there has access to the full range of Bureau of Indian Affairs, Indian Health Services, Housing and Urban Development, as well as the mandatory land into trust provision and the possibility of having reservation lands anywhere in their service area.”

More recently, the Coquille entered an agreement with the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission to co-manage hunting and fishing for Coos, Curry, Douglas, Jackson, and Lane counties.

“It extends to all the counties where they lived in Southern Oregon, even though some were not part of the Coquille territory—that includes Lane County all the way to the crest of the Cascades. Jackson County to the fucking crest of the Cascades. This is an amazing agreement—and it’s unheard of in the United States.

“That’s one thing about Oregon,” Mason continues. “We are willing to try things. There’s a creativity in terms of policy that is just beautiful to see.”

Watching trees grow is our exalted pastime …

Even the sun, so commonly yellow,

shines with emerald hue in our Douglas fir state of mind.

Songs of the Land

Mason has heard that it takes five generations in a place, a title he holds in the PNW, for a person to begin to hear the earth. To know its cadence and stories and significance—and its songs.

It’s what he means when he says that the tribes belong not only in the PNW but also leading alongside our governments. They know what this place has been and can be. They know how to be more than simply stewards of the people and animals, land and rivers, mountains and valleys, desserts and oceans. They know how to act, he says, as brothers and sisters to all of creation.

That recognition is found in the blessing the Warm Springs tribe says before and after every meal: Chúush, meaning water is life.

And it’s found in an anthem of the PNW Mason wrote this year:

We are children of tall of tall forests’ sweet, silver streams.

We are children of great mountains, springs of dreams.

We are children of the vibrant coast called “Left,”

Call us Earth’s own children of the verdant West.

Mason recalls the months he lived in Washington, D.C., and longed so much for home that he would look out his window on cloudy days and see the hills of the Pacific Northwest before realizing they were warehouses or other office buildings.

“You get so homesick for the majesty of the mountains and the trees,” he says. “I need to be around big trees. I need to be around tall waterfalls. I need this inspiration.”

The Pacific Northwest has inspired two albums. The most recent, Seasons of Trouble, was released in September and is available for streaming and at Music Millennium. And his first album, Woodword, is a lovesong to those big trees. He studied music at Evergreen and plays guitar, sings, and wrote the lyrics on his two folksy albums. Songs have titles dedicated to “Hemlock Province,” “Cedar of Sorrows,” and “Douglas Fir State of Mind.” The latter muses:

Watching trees grow is our exalted pastime …

Even the sun, so commonly yellow,

shines with emerald hue in our Douglas fir state of mind.

For Mason, that exalted pastime means paying attention, learning the history, hearing the stories told by the people around him and the terra firma and the big trees and tall waterfalls.

That includes the one told by that sprig of white oak, Quercus garryana. As promised, as we are leaving, Mason shares that tribes may have helped the plant—a native of British Columbia—spread faster south throughout the PNW and as far south as Southern California than it would have on its own. Due to gravity, the seed of the deciduous hardwood naturally only travels a short distance from the crown of the tree. According to Frank A. Lang, “Native Americans used the acorns as a staple food source, eaten raw, or roasted, dried, cooked as a mush, soup, or bread, usually after treating acorns to remove the bitter tannins, a labor-intensive process.”

In eating the seeds, Native peoples may have been responsible for the long-distance colonization, which in turn played an essential role in their survival.

According to an article published by the United States Department of Agriculture, “Oaks were truly the ‘tree of life’ in many Native American cultures. Not only were acorns an essential food source, but every other part of the tree had important uses as well—from the mushrooms growing on old trunks, mistletoe lacing the branches, and galls attached to leaves. From the various parts of oak trees, Indians carved bows; wove baskets; derived medicines for treating sickness; and obtained fire for warmth, cooking, and firing pottery.”

The Kalapuya and Chehalis would burn its wood to keep insects at bay, keep areas open, and promote wildflowers that were important foods. And the western gray squirrel and birds, including dark-eyed juncos, goldfinches, nuthatches, wild turkeys, and pileated woodpeckers make their homes among the Oregon white oaks.

Those pesky Scotch brooms Mason was helping remove? They not only cause Native people’s allergies to act up. According to Cynthia Orlando, they also negatively impact Oregon white oaks by reducing the survival and growth rate of oak seedlings.

But unless you’re able to hear the earth and know of the stories it tells and the history we share, that twig would just be another bunch of leaves. The yellow flowers of the Scotch broom, just another pretty pop of springtime color.

“You get so homesick for the majesty of the mountains and the trees. I need to be around big trees. I need to be around tall waterfalls. I need this inspiration,” Mason says of his reason for returning to the PNW after living briefly in Washington, DC.

According to a 2007 article published by the US Department of Agriculture, tribes across Oregon and Washington ate the acorns of the Oregon white oak, by steaming, roasting, or boiling them—or baking after leaching in blue mud.

PHOTOGRAPH BY YVC BIOLOGY DEPARTMENT / FLICKR

Songs of the Land

Mason has heard that it takes five generations in a place, a title he holds in the PNW, for a person to begin to hear the earth. To know its cadence and stories and significance—and its songs.

It’s what he means when he says that the tribes belong not only in the PNW but also leading alongside our governments. They know what this place has been and can be. They know how to be more than simply stewards of the people and animals, land and rivers, mountains and valleys, desserts and oceans. They know how to act, he says, as brothers and sisters to all of creation.

That recognition is found in the blessing the Warm Springs tribe says before and after every meal: Chúush, meaning water is life.

And it’s found in an anthem of the PNW Mason wrote this year:

We are children of tall of tall forests’ sweet, silver streams.

We are children of great mountains, springs of dreams.

We are children of the vibrant coast called “Left,”

Call us Earth’s own children of the verdant West.

Mason recalls the months he lived in Washington, D.C., and longed so much for home that he would look out his window on cloudy days and see the hills of the Pacific Northwest before realizing they were warehouses or other office buildings.

“You get so homesick for the majesty of the mountains and the trees,” he says. “I need to be around big trees. I need to be around tall waterfalls. I need this inspiration.”

Mason has two albums inspired by his love of the Pacific Northwest. The most recent, Seasons of Trouble, was released in September. Both are available for streaming and for purchase at Music Millenium in Portland.

The Pacific Northwest has inspired two albums. The most recent, Seasons of Trouble, was released in September and is available for streaming and at Music Millennium. And his first album, Woodword, is a lovesong to those big trees. He studied music at Evergreen and plays guitar, sings, and wrote the lyrics on his two folksy albums. Songs have titles dedicated to “Hemlock Province,” “Cedar of Sorrows,” and “Douglas Fir State of Mind.” The latter muses:

Watching trees grow is our exalted pastime …

Even the sun, so commonly yellow,

shines with emerald hue in our Douglas fir state of mind.

For Mason, that exalted pastime means paying attention, learning the history, hearing the stories told by the people around him and the terra firma and the big trees and tall waterfalls.

That includes the one told by that sprig of white oak, Quercus garryana. As promised, as we are leaving, Mason shares that tribes may have helped the plant—a native of British Columbia—spread faster south throughout the PNW and as far south as Southern California than it would have on its own. Due to gravity, the seed of the deciduous hardwood naturally only travels a short distance from the crown of the tree. According to Frank A. Lang, “Native Americans used the acorns as a staple food source, eaten raw, or roasted, dried, cooked as a mush, soup, or bread, usually after treating acorns to remove the bitter tannins, a labor-intensive process.”

In eating the seeds, Native peoples may have been responsible for the long-distance colonization, which in turn played an essential role in their survival.

According to an article published by the United States Department of Agriculture, “Oaks were truly the ‘tree of life’ in many Native American cultures. Not only were acorns an essential food source, but every other part of the tree had important uses as well—from the mushrooms growing on old trunks, mistletoe lacing the branches, and galls attached to leaves. From the various parts of oak trees, Indians carved bows; wove baskets; derived medicines for treating sickness; and obtained fire for warmth, cooking, and firing pottery.”

The Kalapuya and Chehalis would burn its wood to keep insects at bay, keep areas open, and promote wildflowers that were important foods. And the western gray squirrel and birds, including dark-eyed juncos, goldfinches, nuthatches, wild turkeys, and pileated woodpeckers make their homes among the Oregon white oaks.

Those pesky Scotch brooms Mason was helping remove? They not only cause Native people’s allergies to act up. According to Cynthia Orlando, they also negatively impact Oregon white oaks by reducing the survival and growth rate of oak seedlings.

But unless you’re able to hear the earth and know of the stories it tells and the history we share, that twig would just be another bunch of leaves. The yellow flowers of the Scotch broom, just another pretty pop of springtime color.

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

Located near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, the Vancouver Land Bridge merges rivers, land, people, and trade.