A Confluence of Peregrinations and Prayers

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

At Chief Timothy Park in far eastern Washington, basalt benches set amid expansive earth blend pasts and possibilities.

This essay is part of a series on Maya Lin’s Confluence Project, in which I explore the history, heritage, and ecology of five existing sites. You can read more by visiting the Confluence Project series page.

BY LAURA J. COLE | October 8, 2024

We did not follow the river to Chief Timothy Park.

Unlike with the Columbia River in Oregon, no highway in Washington chases the Snake. Not, that is, until you’re thrown out onto its banks less than a mile from the tiny town near the Idaho border where the park—an island—is tethered to the mainland by a small bridge.

Instead of water, we drove beside rolling farmland, dust being kicked up by men clearing fields in preparation of the next round of crops. In truth, we took the least direct path, choosing to drive north, to the basalt canyons of Palouse Falls, before heading southeast. I had been reading Kent Nerburn’s Chief Joseph and the Flight of the Nez Perce leading up to the trip, and it colored my experience of everything I saw.

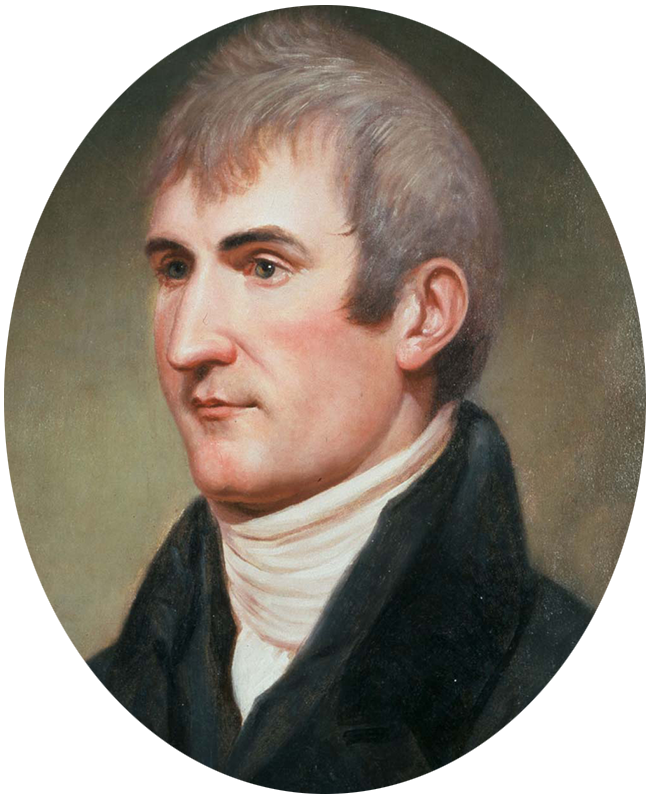

I pictured the Corps of Discovery as the three Nimiipuu* boys did when they first saw the explorers near the Weippe Prairie at the foothills of Idaho’s Bitterroot Mountains: faces “covered in fur like dogs,” eyes “like dead fish,” and “a willingness to eat puppies.” (It’s true. All but Lieutenant William Clark ate dogs when nothing else was available. The accusation, though, made Captain Meriwether Lewis so angry he threw a puppy at a Nimiipuu who made fun of him for it.) Despite or because of Clark’s sunset-colored hair, the young boys were terrified of these men. They had long heard stories about “strange, pale-skinned men coming from the east who would bring sickness and ruin.” A Nez Perce woman named Watkueis, or “She Who Had Returned from a Far Country,” encouraged the tribe to welcome the men, as ones similar to them helped her escape her Blackfeet captors.

And so the Nimiipuu gave them places to stay, taught them to make canoes to navigate their way to the ocean, drew them a map of the river, traveled with them partway to ensure their safe travels among the tribes, and took care of the Corps’ horses during the winter. For their part, the Corps were friendly and generous. They gifted the Nimiipuu guns and ammunition, and Clark taught them how to heal their eye infections and sour stomachs.

But for this tribe, and so many others, the legend would prove prophetic. Only a few decades after Lewis and Clark stopped here, the Nez Perce were driven from their ancestral homelands first by settlers, then by laws, then by militias, being murdered by the thousands by all of them. It’s a devasting tale and even more devasting reality. For me, it’s a history I’m still learning about.

Unlike with the Columbia River in Oregon, no highway in Washington chases the Snake. Not, that is, until you’re thrown out onto its banks less than a mile from the tiny town near the Idaho border where the park—an island—is tethered to the mainland by a small bridge.

Instead of water, we drove beside rolling farmland, dust being kicked up by men clearing fields in preparation of the next round of crops. In truth, we took the least direct path, choosing to drive north, to the basalt canyons of Palouse Falls, before heading southeast. I had been reading Kent Nerburn’s Chief Joseph and the Flight of the Nez Perce leading up to the trip, and it colored my experience of everything I saw.

I pictured the Corps of Discovery as the three Nimiipuu* boys did when they first saw the explorers near the Weippe Prairie at the foothills of Idaho’s Bitterroot Mountains: faces “covered in fur like dogs,” eyes “like dead fish,” and “a willingness to eat puppies.” (It’s true. All but Lieutenant William Clark ate dogs when nothing else was available. The accusation, though, made Captain Meriwether Lewis so angry he threw a puppy at a Nimiipuu who made fun of him for it.) Despite or because of Clark’s sunset-colored hair, the young boys were terrified of these men. They had long heard stories about “strange, pale-skinned men coming from the east who would bring sickness and ruin.” A Nez Perce woman named Watkueis, or “She Who Had Returned from a Far Country,” encouraged the tribe to welcome the men, as ones similar to them helped her escape her Blackfeet captors.

Indigenous land of:

Nez Perce/Nimiipuu

*NOTE: On their tribal website, Nez Perce and Nimiipuu are used interchangeably. I use both here, but it is worth noting that Nimiipuu means “The People.” The name Nez Perce came from 18th-century French Canadian fur traders who called them pierced nose (nez percé), even though nose piercing was never practiced by the tribe.

Image courtesy of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission

And so the Nimiipuu gave them places to stay, taught them to make canoes to navigate their way to the ocean, drew them a map of the river, traveled with them partway to ensure their safe travels among the tribes, and took care of the Corps’ horses during the winter. For their part, the Corps were friendly and generous. They gifted the Nimiipuu guns and ammunition, and Clark taught them how to heal their eye infections and sour stomachs.

But for this tribe, and so many others, the legend would prove prophetic. Only a few decades after Lewis and Clark stopped here, the Nez Perce were driven from their ancestral homelands first by settlers, then by laws, then by militias, being murdered by the thousands by all of them. It’s a devasting tale and even more devasting reality. For me, it’s a history I’m still learning about.

“It takes awhile for people to comprehend this story of the Pacific Northwest.”

—Jane Jacobsen, founding director of the Confluence Project, who petitioned Maya Lin for a year and half to work on the project

For Maya Lin, who launched her career with the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., it’s far from what she wanted the focus of the Confluence Project to be. She has said she’s reluctant to create another monument. She doesn’t want to be remembered solely for memorializing trauma. Instead, she has focused her later works on the environment—how we see it, treat it, and connect with it.

“I get so many proposals I have to turn down,” Lin said in a 2005 article in The Spokesman-Review. “I had retired from the monument business. But [in the years leading up the 200th anniversary of the Corps of Discovery, the tribes] were like: We don’t have that much to celebrate in these last 200 years. Can you give us a reason to celebrate? They asked me because I’m a committed environmentalist. Once I realized it wasn’t about anger, it was more like: What is this about? . . . Can we rethink things we think we already know?”

In fact, Lin turned down the Confluence Project several times over the span of several months. She heard stories and pleas, received maps and phone calls. Then, the organizers sent her a box of materials collected from the sites: a stone, sand, feather, shell, stick, earth. Eventually, she said yes. And that answer brought her here, to this site on a 282-acre island in the Snake River, a stone’s throw from the twin cities of Lewiston, Idaho, and Clarkston, Washington.

Indigenous land of:

Nez Perce/Nimiipuu

*NOTE: On their tribal website, Nez Perce and Nimiipuu are used interchangeably. I use both here, but it is worth noting that Nimiipuu means “The People.” The name Nez Perce came from 18th-century French Canadian fur traders who called them pierced nose (nez percé), even though nose piercing was never practiced by the tribe.

The Nez Perce reservation is dark green and the land they ceded to the United States is light green. The Columbia Basin is dark tan.

Image courtesy of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission

On a sunny morning in June 2005, Lin attended a Nimiipuu blessing ceremony on this spot. With birds overhead and dry fescue, balsam root, and basalt bluffs around them, Lin gathered with others in plastic chairs just beyond the ceremony, where Indigenous women sat on the south, men stood on the north, and elders gathered on the west, leaving the east open to welcome the rising sun. “Uncle” Horace Axtell, a then-80-year-old spiritual leader of the Niimiipuu, rang a bell, sang, prayed, beat a drum, and repeated the word: Qe’ciyew’yew’. He said his ancestors woke every morning and said the word, meaning thank you, to the Creator who gave them language and land.

Lin was moved to tears.

“Would I have even dreamed five years ago I would be part of a Nez Perce blessing ceremony?” she asked in the 2005 article. “What we just witnessed today, I feel an incredible responsibility. Not just sympathy. You feel like working really hard not to disappoint, and that has nothing to do with tourism. It’s on a human level, intimate, about the larger landscape. This place has a power. For me, it’s about the land. For them, it’s the Creator. For everyone, it’s something.”

At the time, she referred to the island’s highest point, which would soon be the site of the subtle amphitheater, as the skybowl—the place where the basalt meets the sky.

I stood in the same spot, nearly 20 years later, on a warm, sunny afternoon in early April. There are a few houses and utility poles on the surrounding bluffs, and I could hear the faint sounds of cars and trucks passing by on the roads on either side of the Snake River. But mostly, I felt far from everything. It is at least a six-hour drive from my home in Portland, by the fastest route. I was there with my partner, John, and dog, Vandy. We saw other people in the parking lot, fishing off the bridge, and lounging along the beach, but only one other couple—young, perhaps in high school or college—later walked out to where we were.

This scenery is similar to so many landscapes I’ve sped past in my car on my way to other places, admiring the undulating curves and blowing grasses while racing to get beyond them. Standing still, I was surrounded by dark water, rolling green hills, and bright blue sky in all directions. The sun glared down on me, with no option for relief. At my feet, spiky grasses grew from hard earth pockmarked with holes. Trees grow along the Snake’s shores, but none extend beyond the parking lot and campgrounds, and thus, provide no shade here.

At the time, she referred to the island’s highest point, which would soon be the site of the subtle amphitheater, as the skybowl—the place where the basalt meets the sky.

I stood in the same spot, nearly 20 years later, on a warm, sunny afternoon in early April. There are a few houses and utility poles on the surrounding bluffs, and I could hear the faint sounds of cars and trucks passing by on the roads on either side of the Snake River. But mostly, I felt far from everything. It is at least a six-hour drive from my home in Portland, by the fastest route. I was there with my partner, John, and dog, Vandy. We saw other people in the parking lot, fishing off the bridge, and lounging along the beach, but only one other couple—young, perhaps in high school or college—later walked out to where we were.

This scenery is similar to so many landscapes I’ve sped past in my car on my way to other places, admiring the undulating curves and blowing grasses while racing to get beyond them. Standing still, I was surrounded by dark water, rolling green hills, and bright blue sky in all directions. The sun glared down on me, with no option for relief. At my feet, spiky grasses grew from hard earth pockmarked with holes. Trees grow along the Snake’s shores, but none extend beyond the parking lot and campgrounds, and thus, provide no shade here.

“This place has a power. For me, it’s about the land. For [the Nez Perce], it’s the Creator. For everyone, it’s something.”

—Maya Lin

Lin has said she wants for this project to “connect you back to the landscape, make you pay a little closer attention to where you are, maybe who you are.” And, indeed, it is easier to focus on all of these things, rather than the reason I came: Lin’s curved basalt benches, arranged in three semicircles, tucked into the earth.

Eventually, I made my way to structures that look not unlike long headstones. Etched into the lowest one facing south are the words: “Of the six Confluence Project sites, this island in the Snake River and its surroundings most closely resemble the landscape seen by Lewis and Clark.” I walked around it, looking for the best angles for photos, but my eyes kept returning to everything else: the bird overhead, the warmth of the sun on my neck and arms, the sound of the river lapping against the nearby shores, the way the light hit the spindly plants whose names I don’t know.

I remember wondering what it would be like to have a home here, and just as quickly wondering why that thought comes so fast, why that reaction is so hard wired. Yes, it is peaceful and lovely here. Now, in early spring. But nothing about this spot gives the impression of making for easy life. The terrain is rough and coarse. The river looks calm, but I have no doubt its currents are not. In the summer, I imagine the heat extracts all possible water from every other available source. A small fire could quickly spread for miles out here. There is no protection from the elements. Wind, rain, fire, snow—all have equal access.

I can’t shake the sense that every part of this place is designed to return to just this. Somehow wide and open, yet tight and closed. It’s not to say we haven’t tried and won’t continue trying. There are houses out on the bluffs and a few tents in the campsites. People live here and always have. Wildlife and plants have adapted to thrive in it.

The young couple who arrived as we were returning to the skybowl from the opposite end of the island are walking hand-in-hand around the amphitheater. Their focus is at least as much on each other as the landscape or basalt. I watch as they take selfies and pose for each other’s phones.

It is true that we all need wide-open yet specific spaces that encourage us to focus on the landscape and each other. To remember what a place once was, what it meant, and has become—and to imagine what it could be.

And likewise, who we are—and could be.

Journal entry

May 4, 1806

“the lands through which we passed today are fertile consisting of a dark rich loam. the hills of the river are high and approach it nearly on both sides. no timber in the plains. … the hills of the creek which we decended this morning are high and in most parts rocky and abrupt.”

—Meriwether Lewis

Did you know?

The Pacific Northwest is home to the youngest, smallest, and best-preserved continental flood basalt province on earth. Known as the Columbia River Basalts (CRBs), they erupted from long fissures in the ground over a period of about 11 million years and extend more than 81,000 square miles across western Idaho, central and southern Washington, and northern and eastern Oregon. It lies beneath the entire route that Lewis and Clark traveled from what is now Idaho to the spot where the Columbia River greets the Pacific Ocean. Lin incorporated this rock in several of the Confluence Projects, including here, at Chief Timothy State Park.

Image of basalt columns at Drumheller Channels National Natural Landmark by Hanjo Hellmann / Adobe Stock

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

Located near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, the Vancouver Land Bridge merges rivers, land, people, and trade.