A Confluence of Peregrinations and Prayers

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

along the

water’s

edge

along

the

water’s

edge

Maya Lin’s Confluence Project traces cultures, history, and ecology across the Columbia River basin in Washington and Oregon. Here’s what it taught me about homeland, heritage, and waterways.

BY LAURA J. COLE | October 7, 2024

Most days, I find it difficult not to think about water—its scarcity, potability, and power.

For the past week and a half, my feed has been full of images of the aftermath of devasting floods across the South, as another hurricane gains strength in the Gulf of Mexico. But nearly a decade ago, in early 2015, I found myself contemplating the history, value, and meaning of a shiny squiggly line. Before me was “Pin River – Yangtze,” a sculpture made of thousands of silver pins that traces the course of the Yangtze River.

The sculpture was one of many focused on the world’s waterways by artist Maya Lin that I encountered that winter. Her exhibition, Maya Lin: A History of Water at the Orlando Museum of Art, featured two-by-four boards of varying heights to mimic the topography of mountains, floating wires bent into the likeness of underwater landmasses, and bodies of water made of pins, silver, and marble. During a lecture, she discussed the rivers, oceans, and lakes that inspired her work as well as her desire to protect them and the species they sustain.

“People focus on what they can see,” Lin said of rivers in a museum piece about the exhibition. “In order to protect it, you have to see it in its entirety.”

I would add, that to want to protect something, you also have to respect it, to understand it. A few years earlier, I learned this lesson during a cruise along the Yangtze River. As I journeyed from Chongqing down the river, I sailed past tributaries, mountains, bridges, and holy temples that had existed for centuries. I also passed by signs marking everything that would soon be under water. This was 2008, a year before the Three Gorges Dam project was set to flood areas upstream from the barrier. Among the largest in the world, the dam was developed to generate electricity, increase shipping capacity, and reduce floods which plagued the plains surrounding the river.

But it would also displace families, destroy homes, and relocate entire villages. The cruise stopped in the largest of those villages, Fengdu, so we could tour homes, markets, and rice fields that were slated to disappear. I met some of the families, and snapped a photo of the shoes they lined up neatly outside of a home that would soon be entirely submerged.

On this trip, I learned many things, including how controlling a river can change it. How, in trying to protect people, you can demolish heritage and homes. And how, often, progress is a name we give to things that erase the past and the valuable things we learned from it.

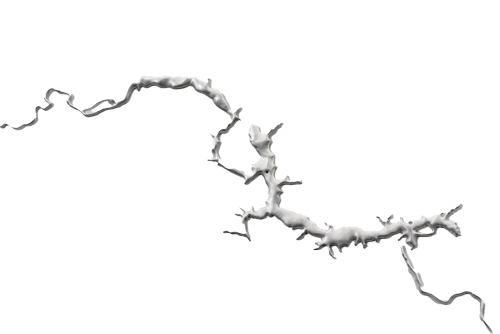

As part of her study of waterways, Maya Lin made several silver sculptures, including of the Missouri River (shown here). It is the fourth longest river in the world, and provided the path Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery Expedition followed along their journey from St. Louis to the Continental Divide.

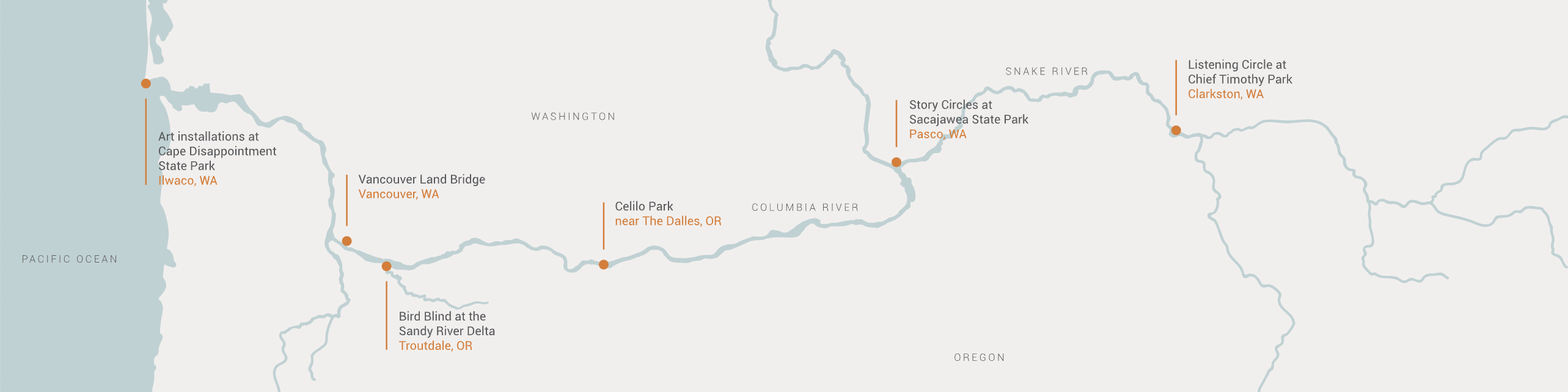

Maya Lin’s Confluence Project features six sites (the one at Celillo Falls is currently on hold) that sit at critical junctions: where the Clearwater River meets the Snake, the Snake meets the Columbia, and the Columbia meets the Sandy, Willamette, and Pacific Ocean. The project spans 438 miles, from the border of Washington in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, juxtaposing the stories of Lewis and Clark’s Expedition with the stories of the people who have lived on these lands for approximately 10,000 years. According to the project’s official website (where this image is from), “the artworks invite you to reimagine our shared environment as it once was and what it could be.”

Maya Lin’s projects ignited a desire to want to learn more about our waterways, and in researching her other work, I came across the Confluence Project, which places Indigenous history alongside that recorded by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark during their Corps of Discovery Expedition. I decided that one day, I would visit each of the sites spread across the Columbia and Snake rivers. Then, having no understanding of how far that distance really is, I thought I could do it in a day. Instead, after moving to Oregon, I ended up visiting each site over the course of two years, beginning where the project starts and the Lewis and Clark Expedition ended—at Cape Disappointment State Park in Washington.

“There is something very important about telling what I call the ‘deeper’ story of a place.”

—Maya Lin

As we approach both the anniversary of Lewis and Clark first entering what is now Washington on October 10, 1805 and the dedication of Cape Disappointment in 2005, here are just a few of the stories I found about the people, plants, and animals that live along and depend upon these mighty rivers.

Names for the Snake River

Snake River, English, likely by European explores who misinterpreted a Shoshone hand sign

Kimooenim, Nez Perce

Yampapah, Shoshoni

Lewis River, English, after Meriwether Lewis

Names for the Columbia River

Columbia River, English, by American captain Robert Gray after his ship, the Columbia Rediviva, crossed the western river’s treacherous bar

Nch’i-Wàna, Sahaptin

np̓k̓ʷátkʷ, Salish

Wimahl, Chinook

Swah’netk’qhu, Sinixt

Q’alawn, Nez Perce

Rio de San Roque, by Spanish captain Bruno Heceta

River Ourigan, by Robert Rogers

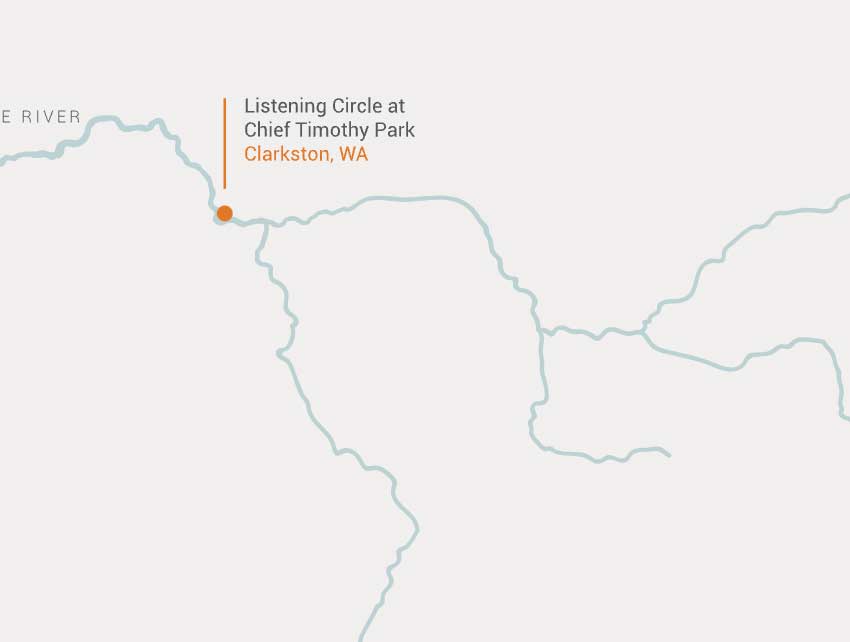

The listening circle in Clarkston, Washington, pays tribute to a Nez Perce blessing ceremony performed in 2005, on the only Confluence site that still resembles what Lewis and Clark would have seen more than 200 years ago.

Read MoreChief Timothy Park

The seven story circles in Pasco, Washington, hint at all that is, was, and could be lost—or saved—by altering a river’s path.

Read MoreSacajawea Historical State Park

Deep in the Sandy River Delta, Maya Lin’s bird blind connects past and present through the animals found all around us.

Read MoreSandy River Delta

Located near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, the Vancouver Land Bridge merges rivers, land, people, and trade.

Read MoreVancouver Land Bridge

Near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s art installations at Cape Disappointment present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

Read MoreCape Disappointment State Park

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

Located near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, the Vancouver Land Bridge merges rivers, land, people, and trade.