A Confluence of Peregrinations and Prayers

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

SHIFTING S A N D S

SHIFTING

S A N D S

A trip to the Oregon Dunes unearthed the influence for Frank Herbert’s Dune—and a love of stories and nature passed down from fathers and places.

BY LAURA J. COLE

February 27, 2024

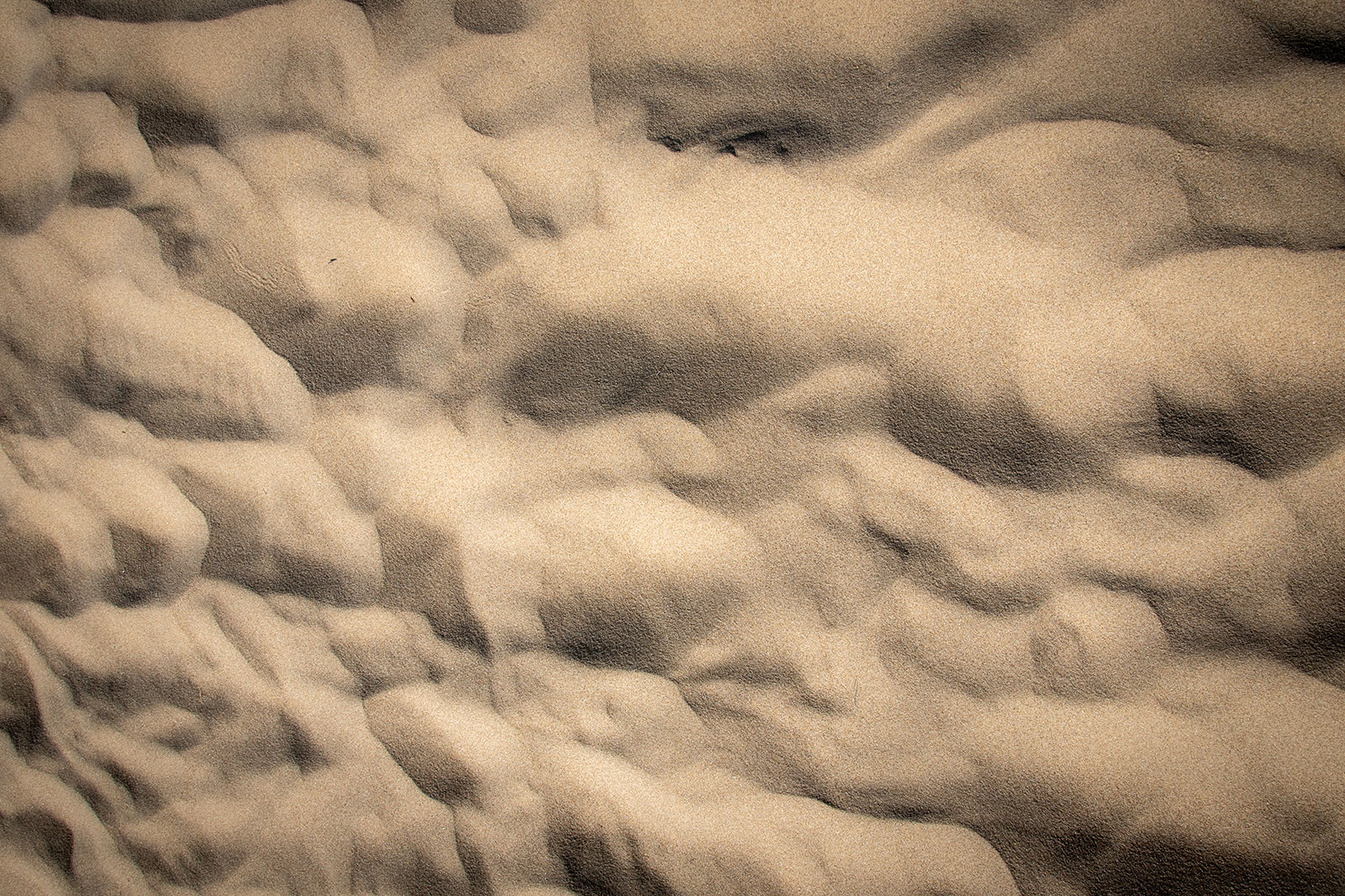

I stood atop the large flattop mound of sand, sensing the grains that were covering me. I could feel them stuck to my bare feet and neck, wedged between my toes and teeth, and embedded in the roots of my pulled-back hair.

They were in the crevices of my glasses and on my camera lens and in all the delicate spaces that move.

I knew my dog fared worse—but she was far from bothered. Running in ever-tightening circles out and back to me along open dunes near Lakeside, Oregon, she ran with abandon: her ears pinned to the back of her head by the resistance of the wind, her mouth wide, her tongue flopping with each gallop.

She was in her happy place.

And so was I.

Over the past four years, she has run across dunes in Indiana, Colorado, New Mexico, and now Oregon. Though the farthest from the home we left behind in Florida, Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area holds the deepest personal connection for me.

It is this landscape, these same sands, that inspired Frank Herbert’s Dune. The science fiction tome loomed large in my childhood home. Not just on the bookshelf, where it and the rest of the series sat my entire life—unless being read. But in my father’s life.

For as long as I can remember, he had encouraged me, my siblings, and anyone who would listen to read it. He even named my sister Jessica, after the protagonist’s mother.

Weirded out by the strange world in the 1984 movie as a kid, I didn’t read the book until I was in college, an English major talking about the Western literary canon, when my dad emphasized that the Nebula- and Hugo-awarding-winning book should be part of it. His reasoning wasn’t focused on those awards or because it was the inspiration—some have argued the entire storyline—for Star Wars and Game of Thrones. But because, as he said to me recently, “it’s just a good story and it’s educational. What else do you read for?”

When I visited the Oregon Dunes back in October, it was on a vacation with him and my family that he had orchestrated, without even knowing the connection to the book. Some destiny—directed by my sister and I living in Portland—prompted him to rent a house near Florence. I learned while researching things to do nearby that it was the same town that Herbert, a Pacific Northwest resident, visited in 1957, and inspired the book that has since been turned into a movie for the third time.

Standing there on sands that connected my new home to his literary one, I knew only that I wanted to learn more—about Herbert, the Dunes, and the things that become part of us.

Oregon Dunes National

Recreation Area

was established

in 1972 as part of the Siuslaw (pronounced

sigh-YEW-slaw)

National Forest.

A trip to the Oregon Dunes inspired Frank Herbert to write the article “They Stopped the Moving Sands,” two short science fiction novels, and the epic-length Dune, which was rejected by more than 20 publishing houses.

I stood atop the large flattop mound of sand, sensing the grains that were covering me. I could feel them stuck to my bare feet and neck, wedged between my toes and teeth, and embedded in the roots of my pulled-back hair.

They were in the crevices of my glasses and on my camera lens and in all the delicate spaces that move.

I knew my dog fared worse—but she was far from bothered. Running in ever-tightening circles out and back to me along open dunes near Lakeside, Oregon, she ran with abandon: her ears pinned to the back of her head by the resistance of the wind, her mouth wide, her tongue flopping with each gallop.

She was in her happy place.

And so was I.

Over the past four years, she has run across dunes in Indiana, Colorado, New Mexico, and now Oregon. Though the farthest from the home we left behind in Florida, Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area holds the deepest personal connection for me.

It is this landscape, these same sands, that inspired Frank Herbert’s Dune. The science fiction tome loomed large in my childhood home. Not just on the bookshelf, where it and the rest of the series sat my entire life—unless being read. But in my father’s life.

For as long as I can remember, he had encouraged me, my siblings, and anyone who would listen to read it. He even named my sister Jessica, after the protagonist’s mother.

Weirded out by the strange world in the 1984 movie as a kid, I didn’t read the book until I was in college, an English major talking about the Western literary canon, when my dad emphasized that the Nebula- and Hugo-awarding-winning book should be part of it. His reasoning wasn’t focused on those awards or because it was the inspiration—some have argued the entire storyline—for Star Wars and Game of Thrones. But because, as he said to me recently, “it’s just a good story and it’s educational. What else do you read for?”

When I visited the Oregon Dunes back in October, it was on a vacation with him and my family that he had orchestrated, without even knowing the connection to the book. Some destiny—directed by my sister and I living in Portland—prompted him to rent a house near Florence. I learned while researching things to do nearby that it was the same town that Herbert, a Pacific Northwest resident, visited in 1957, and inspired the book that has since been turned into a movie for the third time.

Standing there on sands that connected my new home to his literary one, I knew only that I wanted to learn more—about Herbert, the Dunes, and the things that become part of us.

In Dune, Pardot Kynes, the Imperial Planetologist of Arrakis, “talked to the Fremen about … dunes anchored by grass.”

That very image came from efforts to control the powerful combination of wind and sand that altered landscapes and threatened livelihoods along the Oregon coast in the 1950s.

Herbert was doing research in Florence for a story about man versus nature. A team led by the U.S. Department of Agriculture was attempting to stop the blowing sands that swallowed homes, covered roads and railway tracks, and threatened a seaport.

“These waves can be every bit as devastating as a tidal wave in property damage,” he wrote in a letter.

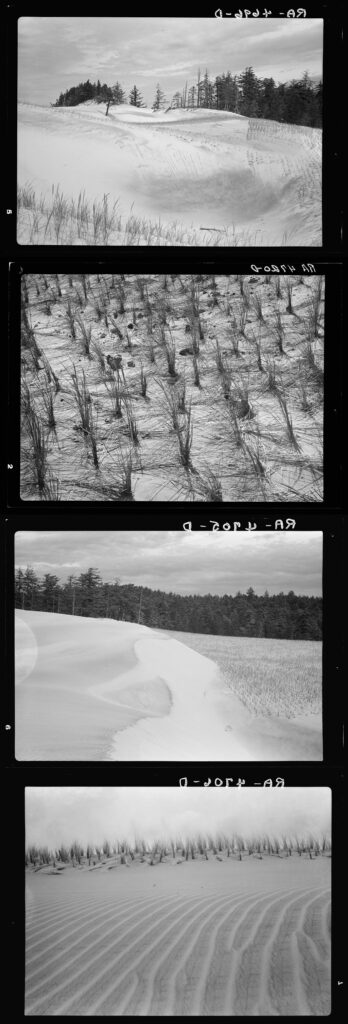

To reduce the effects of that devastation, the group was planting European beachgrass (Ammophila arenaria) to prevent sand from being pushed further inland.

In July 1957, Herbert, who was 40 at the time, chartered a small plane and flew over part of the largest expanse of coastal sand dunes in the United States. What he saw deeply influenced his fictional desert planet and became a major theme of the book: how to alter an inhabitable environment to enable it—and its people—to thrive.

Set in the far future after a huge war between mankind and artificial intelligence, Dune tells the coming-of-age story of Paul, heir to the House Atriedes. As a teenager, Paul and his family move from the verdant planet Caladan to the arid Arrakis, which is known for its prized spice, giant sandworms, Fremen population, and scarcity of water. It is so dry that people must wear stillsuits that collect and recycle body moisture for drinking in order to survive.

After the baron of another prominent house, the Harkonnens, orchestrates the murder of Paul’s father, young Paul is forced into hostile open desert along with his mother, Jessica, who is part of a religious sisterhood with psychic powers known as the Bene Gesserit. Along the way, he must grapple with his destiny of becoming both the Kwisatz Haderach, who the Bene Gesserit prophesize will bridge space and time, and the Muad’dib, who the Fremen view as a messiah.

Well over 100,000 years old and covering more than 30,000 acres, the Oregon Dunes stretch 56 miles from Heceta Head to Cape Arago. And according to the Oregon Dunes Restoration Collaborative, the dunes are comprised of 261 billion cubic feet of sand—enough to fill the Empire State Building 7,000 times over. Each granule is easily lifted by the slightest wind, which on the coast—with its strong winds off the Pacific—creates a landscape and vegetation in constant flux.

The thought in the 1950s, which is now being reconsidered, was that by planting European beachgrass with its roots that can burrow as far as 30 feet into the ground, humans would “deprive the wind of its big weapon: moveable grains,” as Herbert wrote in Dune’s first appendix. Herbert thought this a novel idea, and his resulting magazine article, “They Stopped the Moving Sands,” deemed the efforts “the first enduring answer to shifting sands in all history,” praising it as an “unsung victory in the fight of men against dunes.”

But his proclamation wasn’t historically accurate, and his editor told him he wouldn’t publish the article without more research. By then, Herbert was on to other projects. But as it turned out, his editor was right. This effort in Florence wasn’t the first. The practice dates back two centuries in Europe and had been employed in San Francisco in 1869, when European beachgrass was planted to hold the ground in place and convert the land into what is now Golden Gate Park.

In Oregon, efforts had been made beginning as early as 1910 to tame and alter the dunes. Willow cuttings were planted to create a windbreak. European beachgrass, shrubs, and trees were planted across 47 acres of the dunes. More than three decades later, they were still planting beachgrass to stop the sand from invading recreational campgrounds, forests, agricultural land, and the Oregon Coast Highway.

The Sand Dune Stabilization Project that Herbert witnessed began in 1950 and culminated in European beachgrass being planted along 36 acres of open sand.

The visual of moving sands worked its way into Herbert’s imagination—and novel. After his father’s murder in the book, Paul finds himself with Jessica in a tent buried by sand. Jessica dreams of her dead husband’s name being written in the sand, “the first letter filled before the last was begun.” And the two escape in a ’thopter, or more advanced type of helicopter, by slipping into the sandstorm, described as “a slow clouding of dust that grew heavier and heavier until it blotted out the desert and the moon.”

More than 70 years since that project began and nearly 60 since Dune was published, the saga of man versus nature continues, shifted in some imaginations into a story of man with nature. New questions, such as this one asked by the Oregon Dunes Restoration Collaborative, are being given more consideration: “Can we give the wind reign over the sand again without burying development?”

“The history of dunes allows one to see that they are hybrid entities, shaped by many different forces, beings, and convergences—sea, wind, sand, vegetation, animals, human bodies, perceptions, values, knowledge, policies, fences, and bulldozers,” wrote environmental historian Joana Gaspar de Freitas in “Dune(s): Fiction, history, and science on the Oregon Coast.” “Dunes can be framed by humans, but as they grow, move, transform, or erode, they have a direct impact on humans’ lives. Both humans and dunes affect the plots of each other’s stories.”

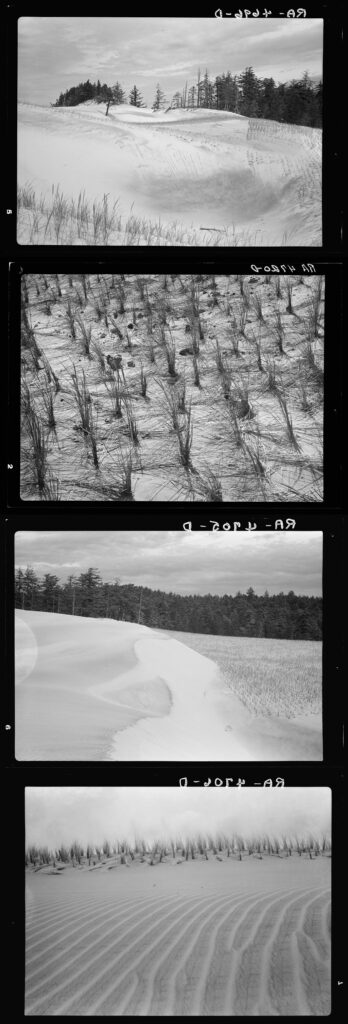

Efforts were made to fix the dunes in place by planting seagrass in the 1930s. These images from 1936 show recent plantings.

Photographs courtesy of Library of Congress

Parts of the dunes are now completely covered in beachgrass, as this one is from the Oregon Dunes Day Use Area near Dune City, Oregon.

“Both humans and dunes affect the plots of each other’s stories.”

In Dune, Pardot Kynes, the Imperial Planetologist of Arrakis, “talked to the Fremen about … dunes anchored by grass.”

That very image came from efforts to control the powerful combination of wind and sand that altered landscapes and threatened livelihoods along the Oregon coast in the 1950s.

Herbert was doing research in Florence for a story about man versus nature. A team led by the U.S. Department of Agriculture was attempting to stop the blowing sands that swallowed homes, covered roads and railway tracks, and threatened a seaport.

“These waves can be every bit as devastating as a tidal wave in property damage,” he wrote in a letter.

To reduce the effects of that devastation, the group was planting European beachgrass (Ammophila arenaria) to prevent sand from being pushed further inland.

In July 1957, Herbert, who was 40 at the time, chartered a small plane and flew over part of the largest expanse of coastal sand dunes in the United States. What he saw deeply influenced his fictional desert planet and became a major theme of the book: how to alter an inhabitable environment to enable it—and its people—to thrive.

Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area was established in 1972 as part of the Siuslaw (pronounced sigh-YEW-slaw) National Forest.

Set in the far future after a huge war between mankind and artificial intelligence, Dune tells the coming-of-age story of Paul, heir to the House Atriedes. As a teenager, Paul and his family move from the verdant planet Caladan to the arid Arrakis, which is known for its prized spice, giant sandworms, Fremen population, and scarcity of water. It is so dry that people must wear stillsuits that collect and recycle body moisture for drinking in order to survive.

After the baron of another prominent house, the Harkonnens, orchestrates the murder of Paul’s father, young Paul is forced into hostile open desert along with his mother, Jessica, who is part of a religious sisterhood with psychic powers known as the Bene Gesserit. Along the way, he must grapple with his destiny of becoming both the Kwisatz Haderach, who the Bene Gesserit prophesize will bridge space and time, and the Muad’dib, who the Fremen view as a messiah.

Well over 100,000 years old and covering more than 30,000 acres, the Oregon Dunes stretch 56 miles from Heceta Head to Cape Arago. And according to the Oregon Dunes Restoration Collaborative, the dunes are comprised of 261 billion cubic feet of sand—enough to fill the Empire State Building 7,000 times over. Each granule is easily lifted by the slightest wind, which on the coast—with its strong winds off the Pacific—creates a landscape and vegetation in constant flux.

The thought in the 1950s, which is now being reconsidered, was that by planting European beachgrass with its roots that can burrow as far as 30 feet into the ground, humans would “deprive the wind of its big weapon: moveable grains,” as Herbert wrote in Dune’s first appendix. Herbert thought this a novel idea, and his resulting magazine article, “They Stopped the Moving Sands,” deemed the efforts “the first enduring answer to shifting sands in all history,” praising it as an “unsung victory in the fight of men against dunes.”

But his proclamation wasn’t historically accurate, and his editor told him he wouldn’t publish the article without more research. By then, Herbert was on to other projects. But as it turned out, his editor was right. This effort in Florence wasn’t the first. The practice dates back two centuries in Europe and had been employed in San Francisco in 1869, when European beachgrass was planted to hold the ground in place and convert the land into what is now Golden Gate Park.

In Oregon, efforts had been made beginning as early as 1910 to tame and alter the dunes. Willow cuttings were planted to create a windbreak. European beachgrass, shrubs, and trees were planted across 47 acres of the dunes. More than three decades later, they were still planting beachgrass to stop the sand from invading recreational campgrounds, forests, agricultural land, and the Oregon Coast Highway.

The Sand Dune Stabilization Project that Herbert witnessed began in 1950 and culminated in European beachgrass being planted along 36 acres of open sand.

The visual of moving sands worked its way into Herbert’s imagination—and novel. After his father’s murder in the book, Paul finds himself with Jessica in a tent buried by sand. Jessica dreams of her dead husband’s name being written in the sand, “the first letter filled before the last was begun.” And the two escape in a ’thopter, or more advanced type of helicopter, by slipping into the sandstorm, described as “a slow clouding of dust that grew heavier and heavier until it blotted out the desert and the moon.”

More than 70 years since that project began and nearly 60 since Dune was published, the saga of man versus nature continues, shifted in some imaginations into a story of man with nature. New questions, such as this one asked by the Oregon Dunes Restoration Collaborative, are being given more consideration: “Can we give the wind reign over the sand again without burying development?”

“The history of dunes allows one to see that they are hybrid entities, shaped by many different forces, beings, and convergences—sea, wind, sand, vegetation, animals, human bodies, perceptions, values, knowledge, policies, fences, and bulldozers,” wrote environmental historian Joana Gaspar de Freitas in “Dune(s): Fiction, history, and science on the Oregon Coast.” “Dunes can be framed by humans, but as they grow, move, transform, or erode, they have a direct impact on humans’ lives. Both humans and dunes affect the plots of each other’s stories.”

In addition to Herbert’s unpublished magazine feature, he turned that trip to Florence into two short science fiction novels and the giant epic we know today. (Which was published after being rejected by more than 20 publishing houses.)

Seven years after it was published in 1965, my dad was a junior in high school in Ohio, when he found the book by chance in a bookstore.

“It was hard to get through the first 100 pages or so,” he said. “But I was captured by the scene when the Mother Superior of the Bene Gesserit tested him—Paul Atriedes—to see if he was human. It just kind of took off from there.”

My dad has since read Dune five or six times and finished reading the whole series—the six novels Herbert himself wrote—recently for the third time.

“It’s a book you definitely have to read twice because there are stories within stories within stories,” he says. “Until you really know who all the characters and all the players are, you really can’t appreciate his thought process going on to write all that stuff. That one guy came up with it all is just astounding to me.”

There’s the environment and efforts to tame it, sure, but there’s also the human story: one filled with philosophy, power struggles, political backstabbing, religion, infighting, and intrigue.

My dad has been rereading the series this time on a Kindle, which has digital notes from Herbert’s son Brian, who has taken the baton from his father in continuing the Dune universe. In addition to writing more novels in the series, Brian wrote a biography about his father and has been advising on the scripts for the recent films by director Denis Villeneuve. In a 2021 interview in Wired, Brian was asked if Dune is a philosophy book or environmental one, and in response Brian mentions an 8 year old he met at a book signing.

“I think that he read it mostly as an adventure story, which is the great story of Paul Atreides,” Brian said. “But there are many more layers, so as you read it again, you might pick up the environmental message or women’s issues in there. Frank Herbert had powerful women not only in this book but in his subsequent ones. Then the politics, the religion. … Dad told me he did that intentionally. He wrote these layers so that you could go back and reread the book. It was kind of a tricky, psychological thing that he did.”

In the same interview, Brian mentions that like so many children, he had no idea at the time who his dad was and what his book meant to so many people. He recalls hitchhiking and talking to the other people in the car when the question came up about what his dad did for a living. Brian mentioned that his dad was a reporter and that he had written some books, including Dune.

“And literally they pulled the car off the road and they looked at me and they said, “Dune?!’” he said. “I had no idea. I was 19 years old. I didn’t know this was a great book.”

Brian acknowledges that his father was complex, sharing that it confounds some people to find out he was a Republican who was also an environmentalist, antiwar activist, and opposed to nuclear power. In 1970, he spoke at the first Earth Day about how important it was to protect the Earth, so future generations could enjoy it.

The landscape, people, and culture of the Pacific Northwest colored so much of Herbert’s experiences and perspective—and that complexity. Here, he met a member of the Hoh tribe who taught him how to fish, subsist from the land, and “the ways of his people.” He wrote for several local papers and spent time as a speechwriter for a Republican senator. When he taught at the University of Washington in the early ’70s, he would take his students camping in the woods.

I learned my love of nature from my own father. As a child in the ’80s, we spent time visiting many of Florida’s natural springs, tubing and canoeing for fun down the clear waters or swimming while my parents learned to scuba dive. My brother and I spent one weekend a month camping with him at different campgrounds around Central Florida as part of Indian Guides and Princesses, a program through the YMCA that because of its offensive name has since been changed to Adventure Guides. When I was in college, he took my sister and me to Yosemite and Glacier national parks, which ignited my love of the West. And one his favorite pastimes is sitting on his porch, listening to music, drinking wine, and watching the sun set over the wetlands. I can still think of few better ways to spend an evening.

His love of nature is a tradition I believe that was passed down to him from his own father, who would take him fishing on remote lakes in central Ontario. And perhaps also from Dune.

Over the years, he persuaded his high school English teacher, his best friend, my mom, my sister, and me to read Dune, which I’m currently doing for the second time. It’s been 20 years since the first time I picked it up, and there’s admittedly so much I forgot or simply didn’t pick up on because of where I was at in my life. The political infighting with painful repercussions for the masses feels annoyingly more poignant. And Arrakis feels more real, more tangible in some ways now since having spent time walking along the dunes, and having felt, as Jessica did, “the sand drag her feet as she climbed.”

In Dune, there is an underlying suggestion that Arrakis—the planet and its vast sands—propelled Paul into the person he became.

As I get older, I can’t help but think about the people, places, and stories that shape and reshape us. Sometimes, they’re experiences like swimming in crystal-clear rivers, traipsing across shifting mountains of sand, and watching the sky change colors as the sun slips behind the horizon. Others, they’re sharing the stories and places that mean the most to us—and having conversations about worlds that inevitably expand our own.

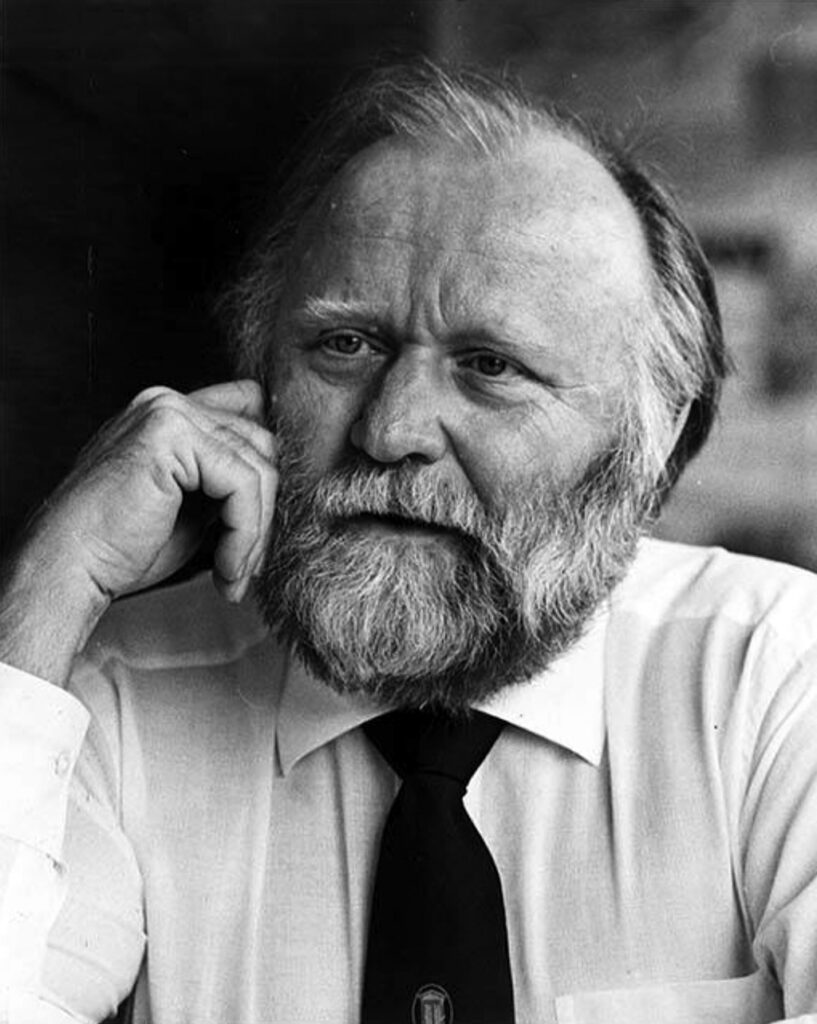

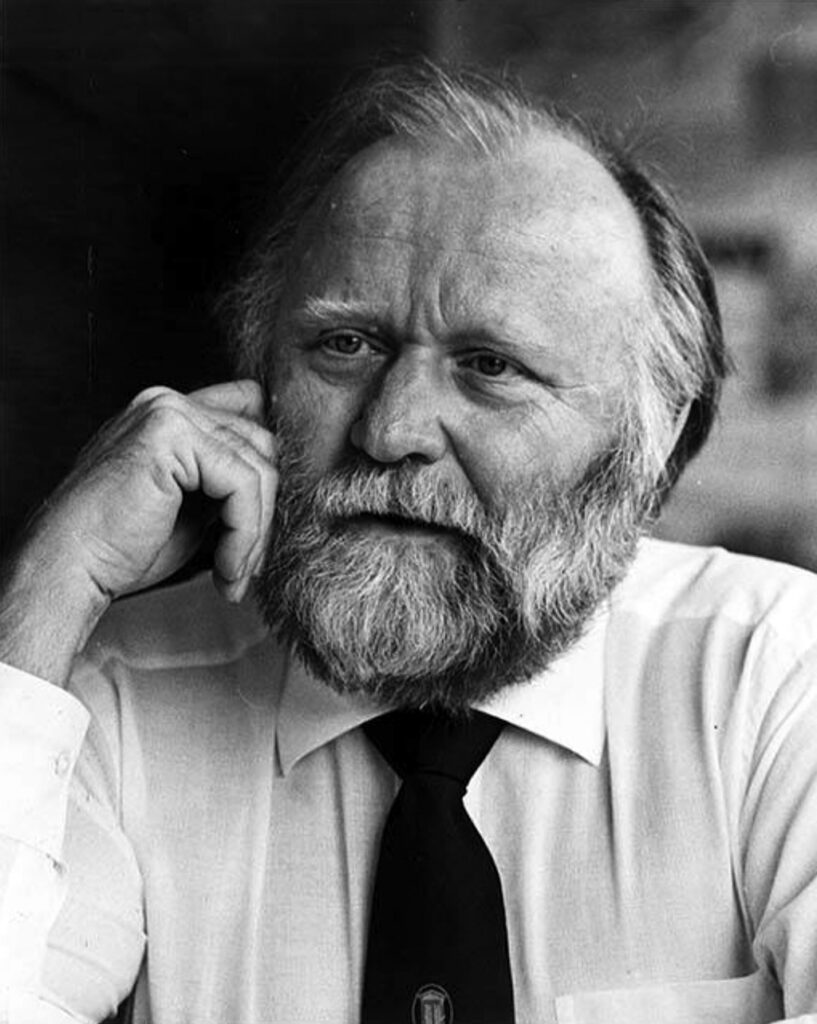

Born in Tacoma, Washington, Frank Herbert grew up an avid outdoorsman. At just 9, he rowed by himself to the San Juan Islands from Tacoma. At 14, he swam across the Tacoma Narrows and later sailed with a friend up to British Columbia and back. He moved to Salem, Oregon, at 17 to live with his aunt and uncle while finishing high school. There, he spent time fishing and hiking in what is now the Three Sisters Wilderness Area.

Named after the representative who introduced the bill that established the park, John Dellenback Trail traverses some of the tallest and most impressive dunes in the area, including this one shown with my dog and partner for scale.

In addition to Herbert’s unpublished magazine feature, he turned that trip to Florence into two short science fiction novels and the giant epic we know today. (Which was published after being rejected by more than 20 publishing houses.)

Seven years after it was published in 1965, my dad was a junior in high school in Ohio, when he found the book by chance in a bookstore.

“It was hard to get through the first 100 pages or so,” he said. “But I was captured by the scene when the Mother Superior of the Bene Gesserit tested him—Paul Atriedes—to see if he was human. It just kind of took off from there.”

My dad has since read Dune five or six times and finished reading the whole series—the six novels Herbert himself wrote—recently for the third time.

“It’s a book you definitely have to read twice because there are stories within stories within stories,” he says. “Until you really know who all the characters and all the players are, you really can’t appreciate his thought process going on to write all that stuff. That one guy came up with it all is just astounding to me.”

“Both humans and dunes affect the plots of each other’s stories.”

There’s the environment and efforts to tame it, sure, but there’s also the human story: one filled with philosophy, power struggles, political backstabbing, religion, infighting, and intrigue.

My dad has been rereading the series this time on a Kindle, which has digital notes from Herbert’s son Brian, who has taken the baton from his father in continuing the Dune universe. In addition to writing more novels in the series, Brian wrote a biography about his father and has been advising on the scripts for the recent films by director Denis Villeneuve. In a 2021 interview in Wired, Brian was asked if Dune is a philosophy book or environmental one, and in response Brian mentions an 8 year old he met at a book signing.

“I think that he read it mostly as an adventure story, which is the great story of Paul Atreides,” Brian said. “But there are many more layers, so as you read it again, you might pick up the environmental message or women’s issues in there. Frank Herbert had powerful women not only in this book but in his subsequent ones. Then the politics, the religion. … Dad told me he did that intentionally. He wrote these layers so that you could go back and reread the book. It was kind of a tricky, psychological thing that he did.”

In the same interview, Brian mentions that like so many children, he had no idea at the time who his dad was and what his book meant to so many people. He recalls hitchhiking and talking to the other people in the car when the question came up about what his dad did for a living. Brian mentioned that his dad was a reporter and that he had written some books, including Dune.

“And literally they pulled the car off the road and they looked at me and they said, “Dune?!’” he said. “I had no idea. I was 19 years old. I didn’t know this was a great book.”

Brian acknowledges that his father was complex, sharing that it confounds some people to find out he was a Republican who was also an environmentalist, antiwar activist, and opposed to nuclear power. In 1970, he spoke at the first Earth Day about how important it was to protect the Earth, so future generations could enjoy it.

The landscape, people, and culture of the Pacific Northwest colored so much of Herbert’s experiences and perspective—and that complexity. Here, he met a member of the Hoh tribe who taught him how to fish, subsist from the land, and “the ways of his people.” He wrote for several local papers and spent time as a speechwriter for a Republican senator. When he taught at the University of Washington in the early ’70s, he would take his students camping in the woods.

I learned my love of nature from my own father. As a child in the ’80s, we spent time visiting many of Florida’s natural springs, tubing and canoeing for fun down the clear waters or swimming while my parents learned to scuba dive. My brother and I spent one weekend a month camping with him at different campgrounds around Central Florida as part of Indian Guides and Princesses, a program through the YMCA that because of its offensive name has since been changed to Adventure Guides. When I was in college, he took my sister and me to Yosemite and Glacier national parks, which ignited my love of the West. And one his favorite pastimes is sitting on his porch, listening to music, drinking wine, and watching the sun set over the wetlands. I can still think of few better ways to spend an evening.

His love of nature is a tradition I believe that was passed down to him from his own father, who would take him fishing on remote lakes in central Ontario. And perhaps also from Dune.

Over the years, he persuaded his high school English teacher, his best friend, my mom, my sister, and me to read Dune, which I’m currently doing for the second time. It’s been 20 years since the first time I picked it up, and there’s admittedly so much I forgot or simply didn’t pick up on because of where I was at in my life. The political infighting with painful repercussions for the masses feels annoyingly more poignant. And Arrakis feels more real, more tangible in some ways now since having spent time walking along the dunes, and having felt, as Jessica did, “the sand drag her feet as she climbed.”

In Dune, there is an underlying suggestion that Arrakis—the planet and its vast sands—propelled Paul into the person he became.

As I get older, I can’t help but think about the people, places, and stories that shape and reshape us. Sometimes, they’re experiences like swimming in crystal-clear rivers, traipsing across shifting mountains of sand, and watching the sky change colors as the sun slips behind the horizon. Others, they’re sharing the stories and places that mean the most to us—and having conversations about worlds that inevitably expand our own.

At Cape Disappointment near the mouth of the Columbia River, Maya Lin’s walkway and boardwalk present juxtaposing journeys of discovery.

Located near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, the Vancouver Land Bridge merges rivers, land, people, and trade.